Reflexivity and participation in communities

6. The Reflexive Participative Partnership (RPP) scheme

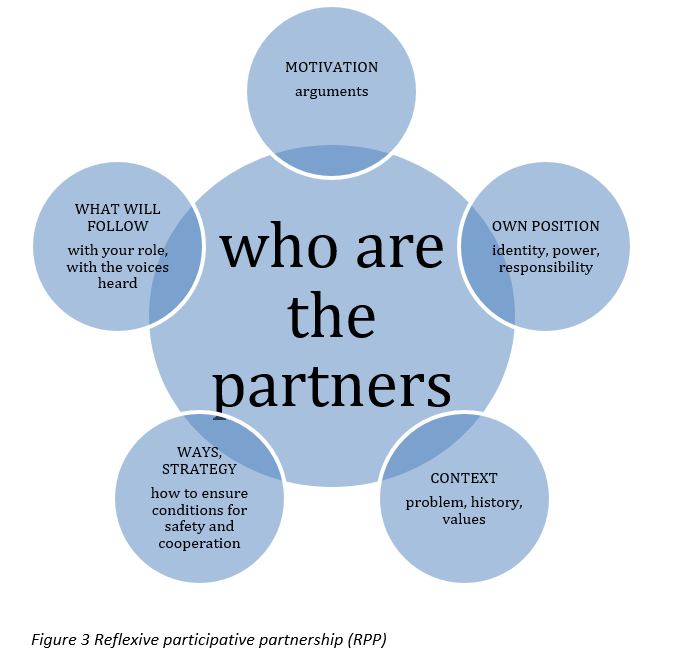

Based on our collective experience during discussions and the development of national case studies, we have identified six aspects of Reflexive Participative Partnership (RPP) that helped us to present complex processes in schematic form. We suggest keeping these six packages in mind when preparing for a collaborative activity. Each partner can construct and reflect on their own six packages, including their motivations, view of their partners, and more). Sharing and discussing these packages can help clarify different views, common goals, and expected benefits of the partnership. RPP should be viewed as a virtual field in which a circular process of reflection on different aspects/packages is constantly ongoing. Each aspect package should be revisited and reflected upon repeatedly to build a better reflective participative partnership continually. This open-ended process contains many challenges and may encounter mistakes, and therefore has the character of a "life-long learning" process.

The motivation for reflection in the RPP scheme is generally the encounter with inequality in status, power or knowledge or difference in attitudes, which you decide to challenge collaboratively. To this aim, we placed the question WHO ARE THE (POTENTIAL) PARTNERS at the centre of the inquiry. It concerns the identification of potential partner/s whom we want to invite into the Reflexive Participative Partnership to challenge their position of inequality. For instance, case studies presented during our project highlighted different partners, such as

- Street-level workers in Finland who worked with clients facing poverty and needed to understand their values during the Covid-19 restrictions. Case study (Finland): Reflexive discretion and social assistance in adult social work in acute and chronic crises.

- Lecturers and students in Ireland have chosen mothers with acquired brain injury as their partners. Case study (Ireland): Working with mothers with acquired brain injury: challenging their unequal status, a framing of their identity as mothers who continue to give care and disabled people who receive care.

- A collective in the Czech Republic has chosen as partners people who have spent a long time in various "homes ", psychiatric hospitals and other asylums. Stories for human rights

In some cases, a partnership involves multiple actors, such as teachers, students, and young people from minority groups or the physiotherapist, a patient with chronic pain, and a network of partners from various professions (as exemplified below).

When considering potential partners for collaboration, it is important to recognize and challenge any biases or lack of understanding we may have towards certain groups. They can be service users from marginalized communities (such as Roma / Sinti or travellers, young people or women in recovery from addiction, lonely older people, people with chronic mental illness etc.) or professionals from different fields (i.e., social workers, nurses, medical doctors etc.). In cases when this becomes apparent, deliberately involving individuals with diverse experiences can help overcome misunderstandings or lack of empathy towards their position or needs. In such situations, it may be beneficial to begin the RPP process by reflecting on the CONTEXT and MOTIVATION before identifying and contacting PARTNERS.

Although there are many examples of positive, participatory engagement with service users, there are situations where the conventional process to 'invite' participation may have little meaning for those whom we would like to approach. This requires an examination of underlying issues, for example, their own values and priorities, past experiences of tokenism or even risks of harm we are unaware of and against which they need to defend themselves. Participation must always be collaboratively negotiated and not enforced.

To identify partners and build trustful relationships, the RPP process suggests that we listen to the potential partner's experiences to understand them better, whether they are service users, other professionals or other groups (Package: PARTNERS). By doing so, we can motivate them to collaborate and move forward with arguments they understand (Package: MOTIVATION). We must also appreciate non-participation or "refusal to participate" as a form of agency, as it represents a position-taking towards services and society in general and may be an attempt to influence public debate on social issues and express a valuable voice.

To effectively engage in reflexive participatory practices, the RPP packages suggest that we reflect on our own motivation, position, and values (Package: OWN POSITION) and try to understand the context of both ourselves and our potential partners, including their individual and collective memories and experiences (Package: CONTEXT).

These considerations are crucial for developing a trustful relationship with our partners, both before and after the collaboration has begun (see link safe environment). This ensures participation is built on common motivation, trust, and mutually meaningful partnership (Package: WAYS AND STRATEGIES).

It is also important to consider what will happen after the common goal has been reached, who is expected to implement potential results, how long we plan to be engaged in the collaboration, and what impact we expect for the participants when it ends (Package: WHAT WILL FOLLOW). Reflecting on these questions periodically during the process can help ensure that the collaboration remains on track and meets everyone's needs.

However, it is important to be aware that national and local conditions for participation in education and other activities in the field of social work vary widely (see the package CONTEXT). While some countries have incorporated the participation of citizens as service users into legislation or educational regulations (Fung, 2006; Krumer-Nevo, 2005, 2008; Ní Shé et al., 2019), others may exclude certain groups from participation or value their knowledge as inferior to standardized academic procedures. These aspects of the local CONTEXT should also be made explicit to participating partners before starting any exercise on reflexive collaboration, including teachers, students, and service users.

Guiding questions:

|

|

Here are three examples of how to put the RPP principles into practice. The first example demonstrates how to develop a social and health RPP with a client with chronic pain. The second example showcases how teachers and students in Ireland worked together to develop a course with women in recovery from addiction. Lastly, the third example discusses participative research practices in Belgium.