The Practice Guide

| Site: | MOOC Charles University |

| Course: | Reflexivity and participation in communities |

| Book: | The Practice Guide |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 1 January 2026, 4:11 PM |

Description

Table of contents

- 1. Practice Guide

- 2. Introduction – why participation and reflexivity?

- 3. What's Inside This Practice Guide (PG)?

- 4. Participation and reflexivity – preparatory considerations for the exercises

- 5. How we understand participation

- 6. The Reflexive Participative Partnership (RPP) scheme

- 7. Putting RPP principles into social and healthcare practice

- 8. Putting RPP principles into educational practice

- 9. Participative research through RPP – Guiding questions

- 10. GUIDING QUESTION FOR YOUR OWN EXERCISE IN RPP

- 11. Conclusion

- 12. References

1. Practice Guide

Innovation by supporting reflexivity and participation (INORP): Strengthening education and professionalization of social work on the border of other professions

PRACTICE GUIDE

2. Introduction – why participation and reflexivity?

We all probably already work with the concepts of participation and reflexivity and have considerable experience and a well-grounded understanding of them. However, when the international consortium designing this guide started to discuss the concepts and particularly their practice among the partners from five countries, we had to revisit some very fundamental questions and complex issues. This guide is intended to share these insights with colleagues irrespective of their level of experience with participative approaches.

|

Our first question was: why promote participation and reflexivity in professional education, and why to consider both in relation to each other? |

Our premise is that social workers have an important role as professional partners of disadvantaged, frail, and health-challenged people who are at risk of being excluded from full citizenship in society and of not having a "voice". Kessl (2009) asserts that social work should act as a critical agency, an agency oriented at offering or creating new options to service users which they had previously missed or been denied. They are frequently confronted with offers of solutions to their difficulties on which they were not consulted and over which they have no control. Largely as a result of the lobbying by self-help and service user movements, their participation in social work practice development, social work research, and social work education on topics affecting their lives is being incorporated into the legislation of several countries. Various forms of participative practice have already been developed (see Fung, 2006; Krumer-Nevo, 2005, 2008; Ní Shé et al., 2019). In the drive to make services more responsive to the concerns of 'welfare recipients' as service users, their participation has been recognized as a contribution to the democratization of public service delivery regimes (Beresford, 2010; Garrett, 2019). This progress relates to the wider "participatory democracy turn", which has also become part of the public mandate of social work since the 1990s (Beresford, 2010; Garrett, 2019).

The concept of participation can be summed up as all people "having a voice". Expressing one's voice has become a core attribute of modern citizenship, as the idea of autonomy and participation in public life has evolved since the era of the enlightenment. However, reflections on historical and contemporary transformations of welfare approaches make clear that all versions of citizenship and rights were established only gradually and remained only partially granted to certain sections of the population (Kessl, 2009; Dewanckel et al., 2021). Citizenship and rights were only extended as consequences of social and political struggles in which social movements like the labour, feminist, civil rights, children's rights, and disability rights movements played a key role. However, forms of insecure citizenship, or so-called 'denizenship' (Turner, 2016), are currently of great concern to social workers. Recent neoliberal policies contribute to the erosion of protective structures and solidarity towards citizens. When people have formal but not substantiated citizenship rights, or lack citizenship rights totally as migrants according to the prevailing territorial logic, it is the task of social workers to make citizenship a lived experience. Creating opportunities for real participation in public life, and hence also in educational processes, assumes great political significance. As the value of participation has been raised in relation to service users, it has soon become clear that the inequality also concerns other fields of relationships in professional work – for example, the inequality between social and health care workers, between nurses and medical doctors, between field workers and managers etc. Therefore, in this project, all kinds of situations and examples were discussed, where reflexivity and participation can contribute to better collaboration.

The social and political transformations highlight that when social workers practice participatively, they have to be prepared to encounter conflict in practice as well as in education. Taking participation seriously means being prepared to challenge and confront norms, power structures and power relationships, and systemic inequalities. "Agency" through participation carries a pedagogical mandate: how to facilitate people to have a "voice". "Taking voice" transforms private concerns into public issues and necessarily involves a complex public and democratic learning process in which social work plays an important part (Grunwald & Thiersch, 2009). Our proposals for ways of enhancing participation in social work education are therefore intricately linked to promoting reflective competences. These recognize the complexity of change processes which span from the individual and psychological level to the structural and political sphere.

We observed in what forms principles of participation can be detected in practice, research and education in social work in the 5 countries of the consortium. We concluded that in all cases, they are framed by political agendas centred on status or power issues. These agendas can either promote or impede the development of meaningful approaches to participation. Hence, we conclude that each course and research programme need to carefully analyze those framework conditions to be able to develop an independent and critical position towards such influences. The dynamic interplay is summarised in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: The 'triangle' of teaching, research, and practice with a focus on power aspects in O1)

The value of participation, which expresses the ethos of democracy, can be easily subverted and reduced to mere tokenism, a danger which was noted in all countries participating in this project. It has parallels with a trend towards the tokenistic and populist erosion of democracy itself (Rosanvallon, 2011). One of the hallmarks of professional social work is the recognition of the rights of service users as full citizens whose voice has a decisive and not just consultative influence on decisions concerning their lives.

Link to Lay or/and professional

In some cultural and national contexts, this orientation finds expression in social pedagogical approaches. Social pedagogy seeks to engage people of all ages in life-long, mutual learning projects where informal and formal sources of knowledge and experience are brought together participatively (Köngeter & Schröer, 2013).

For professional social work, participation does not negate the existence of differences in knowledge, power and resources. Instead, it raises the question of to which extent excluded, marginalized, and powerless people can be facilitated to make use of available resources as of right without becoming dependent on support. This ambiguity is inherent to the public mandate of social work and therefore can only be constructively and situation-specifically resolved through reflexivity. When dealing with complex issues, like how to recognize one's own preconceptions, facing the history and context of problematic social conditions, addressing power relations transparently and promoting realistic possibilities of change, reflective competences are needed to make participatory practice meaningful at every step. When we subject our professional methods and strategies to the scrutiny of service users, a reflective dialogue can be generated that enables both "experts" and service users to critically review routine coping strategies and to learn new skills as a result.

Link to Struggle of professional social work with complexity, ambitious expectations and blaming

Participation and reflexivity are understood in this Practice Guide as twins, necessary to be learned and developed continually together with the relevant partners in health and social work education, practice and research.

3. What's Inside This Practice Guide (PG)?

This PG presents the key ideas and principles that emerged from the intercultural dialogue among project partners. These ideas are aimed at helping teachers, students, service users, and service providers apply participation and reflexivity in their collaboration towards common goals.

Throughout the INORP project, we collected knowledge and examples of practices that value participation in education, research, and practice development from several European countries. The Practice Guide builds on three outputs of the INORP project and outlines the opportunities and pitfalls of participatory approaches.

The PG is an important resource for those seeking to engage in collaborative partnerships that foster participation and reflexivity. It offers practical insights and guidance to help educators, researchers, and practitioners create effective and sustainable participative projects that meet the needs of service users and promote social justice. We hope that this guide will inspire you to explore participatory approaches in your own work and contribute to a more democratic and inclusive society.

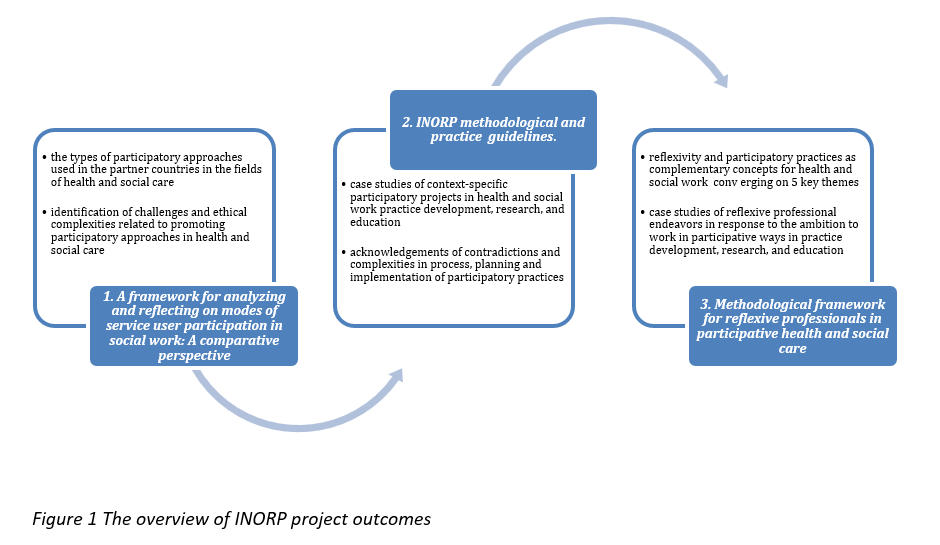

Figure 1 presents an overview of the INORP project outcomes. The full version of the materials of all these phases is available in English on each partner's website (see here). This Practice guide is available at the link to MOOC (Charles University) in English, Czech and Portuguese. Some parts of the materials are delivered as hypertexts of this Practice Guide, mostly in English.

| Output 1 | A framework for analysing and reflecting on modes of service user participation in social work: A comparative perspective |

| Output 2 | INORP methodological and practice guidelines |

| Output 3 | Methodological framework for reflexive professionals in participative health and social care |

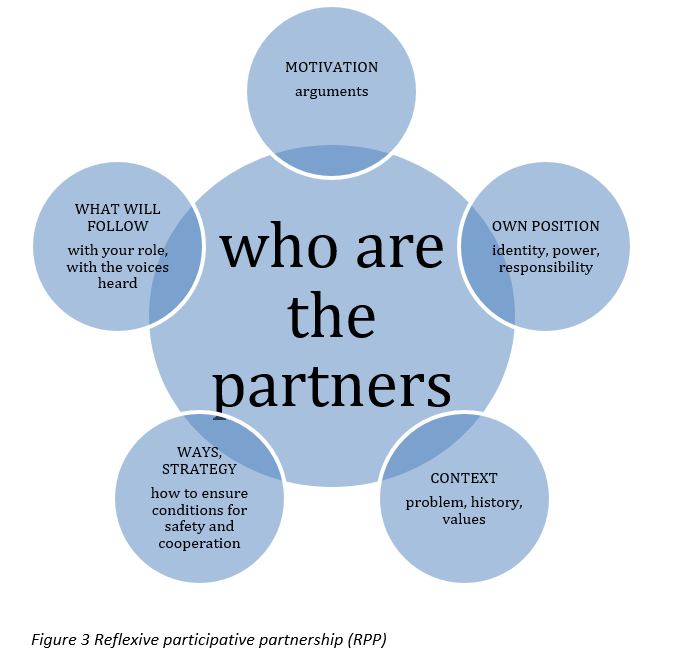

The INORP project material was designed to be accessible not only to academics but also to service users and practitioners. To help us organize the complex issues and materials produced during the project, we summarised our learning in a graphic scheme called the Reflective Participative Partnership (RPP) (see Figure 3). We then used RPP to explain the application of participatory practice in three concrete examples: one from a practice context, one from an educational context, and one from participative research practice.

The RPP format is further accompanied by guiding questions, which can be used as an exercise in various learning contexts, such as a classroom, a walking seminar, or a community group discussion. By following these guiding questions, individuals can create their own participative projects and use the RPP scheme to help guide their practice.

We believe that this material can be further modified, translated, and enriched to make it more accessible to a wider audience in various contexts. We encourage you to adapt the material to your specific language and audience and use it to promote participatory practice in your own community.

Through discussions with students, public service organizations, service user organizations, and social work educators from Belgium, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, and Portugal, we learned that there are significant differences in traditions and developments regarding user involvement and citizen participation across these countries. These differences should be reflected in each social work initiative. To facilitate this consideration, we suggest that teachers and students of social work engage in reflection and analysis by addressing the following three questions before beginning any exercise on participation and reflexivity:

- What is the role of social workers in promoting user involvement/participation in your country?

- How does this relationship reflect the connection between social work, practice, and research in your country?

- Who is involved in facilitating/promoting user participation in your country?

After discussing these questions, we encourage you to explore the result of the comparison of the five partner countries by following this Link to O1

4. Participation and reflexivity – preparatory considerations for the exercises

Before we present a more structured exercise in collaborative participation, we first list motivating ideas and topics that we have developed through three years of discussion.

Our initial literature review (Blomberg et al., 2022) and subsequent discussions with project partners have shown that participation is a fluid and highly situated form of practice. It is more akin to a spiral or multilevel field than a ladder that citizens or practitioners can climb to higher levels (Arnstein 1969).

Based on our experience, we recognize that participants in all collaborative activities bring multiple perspectives and positions arising from their different life and professional experiences. This variety of motivations, aspirations and learning styles creates a rich yet demanding environment for collaborative learning. Each participant gains their own knowledge, and there are also collective insights from practical activities. However, this requires continuous clarifications of what is happening through individual and collective reflexivity (see Figure 2).

| Reflexivity is not only a personal and pedagogical professionalization process but must also consider the organizational, policy and socio-political circumstances in which professionals operate and in which service users are expected to 'participate' (Garett, 2019). We, therefore, include in our concept of reflexivity a personal, interpersonal, and socio-structural dimension (see Van Beveren et al., 2018). | |

|

At the personal level, reflexivity refers to a critical interrogation of one's professional assumptions, of the process of constructing professional knowledge and of how power is at work in it (D'Cruz et al., 2007; Taylor & White, 2001). |

|

At the interpersonal level, reflexivity refers to the process of constructing knowledge about clients and their experiences in dialogue with them (Parton & O'Byrne, 2006). |

|

Finally, at the socio-structural level, reflexivity refers to connecting personal and interpersonal reflections on professional practice with more structural and political analyses of how social problems arise. It helps to place these problems within their historical, socio-political, and socioeconomic contexts. This should be done with a commitment towards social transformation (Bay & MacFarlane, 2011; Brookfield, 2009; Fook, 2016; Van Beveren et al., 2022). |

| Reflexivity also involves an aspect of self-reflection concerning one's own identity, role, personal attitudes, dispositions and experience of situations and relationships, which have an impact on one's decisions and behaviour towards others. | |

Figure 2: Three levels of reflexivity.

|

Our learning can be summarised in the following points: |

How we understand and use reflexivity

In practice and education, there are different notions of reflexivity that vary across different contexts and perspectives (D'Cruz et al., 2007; Fook et al., 2006). Our project has provided us with an opportunity to reflect on these different notions and explore their application in social work practice.

Through the qualitative analysis of various transnational case studies, we have come to link reflexivity in social work to democratic, participatory practice as complementary concepts. By combining these concepts, we can better understand the (inter)personal and structural dimensions of social work practice and create a more inclusive and sustainable approach that values the voices and experiences of service users.

First, we became aware of how our different historical and socioeconomic country backgrounds influenced our thinking. We realized that we sometimes take our own backgrounds for granted and fail to reflect on the differences that exist between us (see Output 1). As a result, we propose that the first step in reflexive collaboration should be to reflect on OUR OWN POSITION.

This reflection leads us to consider the CONTEXT in which people encounter inequality. This involves examining the history, habits, discourses, and solutions that shape problematic social situations. It also provides important insights into how different European countries understand participation and reflexivity in social work education.

As we reflected on our own position and the context in which we work, we identified five central themes that are essential reference points for social work practice. For each theme, we suggest questions for reflection and provide links to case studies that illustrate the issue and help clarify it:

1) Reflexive professionalization is a hallmark of professional practice that promotes critical and productive ways of dealing with the ambiguities, tensions, and challenges that arise in participative health and social care. By engaging in reflexive professionalization, practitioners can reflect on their own assumptions and biases and identify potential power imbalances and conflicts that may arise in collaborative settings.

|

|

Links to case studies and questions: How partners in the project engaged with the challenge of educating students in health and social care to become reflexive professionals that include in their reflexivity a commitment to service-users as citizens.

2) The importance of historical awareness in developing a professional identity and mandate of social workers has been and is currently defined. Different historical periods saw social work as a "tool" with which to achieve particular outcomes. Professionals have to be aware of this pressure and take a position towards it in order, for instance, to understand the reluctance of some service users to collaborate with social workers.

|

|

3) The need to deal with the value orientations of professional practice. All professional associations lay down codes of ethics, but the principles and criteria laid down there need to be related to practice in a continuous process of reflexivity. Participatory practice forms often reveal discrepancies and conflicts between different normative principles.

|

|

4) The need to reflect on how professionals construct problems and interpret service users' voices and lived experiences. Professional practice does not necessarily mean satisfying service users' wishes, yet their articulation of needs can challenge our professional presuppositions.

|

|

5) The necessity of creating space for ambiguity, risks, and mistakes in professional practice. Despite the widespread emphasis on "risk reduction" in service organizations, reflecting openly on ambiguity and mistakes can offer significant learning potential and affirm professional autonomy. Participative approaches invariably imply making mistakes, and it's important to confront them openly and positively. By doing so, social workers can develop a deeper understanding of the complexities of social and health issues, build trust with service users, and foster a more responsive and effective approach to practice.

|

|

5. How we understand participation

|

Participation refers to equal power relations in the situation of decision-making. Participatory approaches challenge professionals to view social problems from the perspectives of others, including service users, rather than imposing their own construction of problems on them. Imposing their own perspectives, for example, on how marginalization occurs, denies service users the chance to exercise their own agency. |

Instead, professionals can act as allies of service users in identifying, defining, and tackling their problems and concerns.

Solving social questions is not a technical matter, and the prerogative of "experts" implies controversy, risk-taking and dealing with conflict. Acknowledging ambiguity and mistakes in this process allows for the sharing of responsibilities between different professionals and service users.

Raising questions in a climate of trust among stakeholders holds the potential to shift taken-for-granted meanings and solutions towards new power constellations and a fairer distribution of responsibilities.

Participation is not a value per se but needs to be related to democratic values and purposes, which need to be agreed with and made explicit to all partners and reflectively applied to the situation.

A highly prescriptive approach can easily cause misunderstandings and misuse of participation, as widely described in the literature (Beresford, 2010; Roets et al., 2012; Adams, 2017). There is a risk of participation becoming otherwise:

- "tokenistic" (Beresford, 2010) due to "service users functioning as pawns rather than pioneers" (Roets et al., 2012),

- "only ad hoc and inconsistent", thereby denying service users the opportunity of drawing their own conclusions from experience and making this a moment in life-long learning (Schön, 2016),

- "more rhetoric than reality" and therefore not showing any noticeable consequences (Adams, 2017),

- a mere "buzzword" that satisfies only superficial criteria without touching issues of power inequalities (Cornwall & Brock, 2005),

- "reproducing subordination, inferiority, and powerlessness" because the issue of power in helping relationships is not being addressed openly and critically (Boone et al., 2019),

- a "new tyranny" that legitimizes an unjustified exercise of power (Cooke & Kothari, 2001) in social policy-making and social work practice development.

6. The Reflexive Participative Partnership (RPP) scheme

Based on our collective experience during discussions and the development of national case studies, we have identified six aspects of Reflexive Participative Partnership (RPP) that helped us to present complex processes in schematic form. We suggest keeping these six packages in mind when preparing for a collaborative activity. Each partner can construct and reflect on their own six packages, including their motivations, view of their partners, and more). Sharing and discussing these packages can help clarify different views, common goals, and expected benefits of the partnership. RPP should be viewed as a virtual field in which a circular process of reflection on different aspects/packages is constantly ongoing. Each aspect package should be revisited and reflected upon repeatedly to build a better reflective participative partnership continually. This open-ended process contains many challenges and may encounter mistakes, and therefore has the character of a "life-long learning" process.

The motivation for reflection in the RPP scheme is generally the encounter with inequality in status, power or knowledge or difference in attitudes, which you decide to challenge collaboratively. To this aim, we placed the question WHO ARE THE (POTENTIAL) PARTNERS at the centre of the inquiry. It concerns the identification of potential partner/s whom we want to invite into the Reflexive Participative Partnership to challenge their position of inequality. For instance, case studies presented during our project highlighted different partners, such as

- Street-level workers in Finland who worked with clients facing poverty and needed to understand their values during the Covid-19 restrictions. Case study (Finland): Reflexive discretion and social assistance in adult social work in acute and chronic crises.

- Lecturers and students in Ireland have chosen mothers with acquired brain injury as their partners. Case study (Ireland): Working with mothers with acquired brain injury: challenging their unequal status, a framing of their identity as mothers who continue to give care and disabled people who receive care.

- A collective in the Czech Republic has chosen as partners people who have spent a long time in various "homes ", psychiatric hospitals and other asylums. Stories for human rights

In some cases, a partnership involves multiple actors, such as teachers, students, and young people from minority groups or the physiotherapist, a patient with chronic pain, and a network of partners from various professions (as exemplified below).

When considering potential partners for collaboration, it is important to recognize and challenge any biases or lack of understanding we may have towards certain groups. They can be service users from marginalized communities (such as Roma / Sinti or travellers, young people or women in recovery from addiction, lonely older people, people with chronic mental illness etc.) or professionals from different fields (i.e., social workers, nurses, medical doctors etc.). In cases when this becomes apparent, deliberately involving individuals with diverse experiences can help overcome misunderstandings or lack of empathy towards their position or needs. In such situations, it may be beneficial to begin the RPP process by reflecting on the CONTEXT and MOTIVATION before identifying and contacting PARTNERS.

Although there are many examples of positive, participatory engagement with service users, there are situations where the conventional process to 'invite' participation may have little meaning for those whom we would like to approach. This requires an examination of underlying issues, for example, their own values and priorities, past experiences of tokenism or even risks of harm we are unaware of and against which they need to defend themselves. Participation must always be collaboratively negotiated and not enforced.

To identify partners and build trustful relationships, the RPP process suggests that we listen to the potential partner's experiences to understand them better, whether they are service users, other professionals or other groups (Package: PARTNERS). By doing so, we can motivate them to collaborate and move forward with arguments they understand (Package: MOTIVATION). We must also appreciate non-participation or "refusal to participate" as a form of agency, as it represents a position-taking towards services and society in general and may be an attempt to influence public debate on social issues and express a valuable voice.

To effectively engage in reflexive participatory practices, the RPP packages suggest that we reflect on our own motivation, position, and values (Package: OWN POSITION) and try to understand the context of both ourselves and our potential partners, including their individual and collective memories and experiences (Package: CONTEXT).

These considerations are crucial for developing a trustful relationship with our partners, both before and after the collaboration has begun (see link safe environment). This ensures participation is built on common motivation, trust, and mutually meaningful partnership (Package: WAYS AND STRATEGIES).

It is also important to consider what will happen after the common goal has been reached, who is expected to implement potential results, how long we plan to be engaged in the collaboration, and what impact we expect for the participants when it ends (Package: WHAT WILL FOLLOW). Reflecting on these questions periodically during the process can help ensure that the collaboration remains on track and meets everyone's needs.

However, it is important to be aware that national and local conditions for participation in education and other activities in the field of social work vary widely (see the package CONTEXT). While some countries have incorporated the participation of citizens as service users into legislation or educational regulations (Fung, 2006; Krumer-Nevo, 2005, 2008; Ní Shé et al., 2019), others may exclude certain groups from participation or value their knowledge as inferior to standardized academic procedures. These aspects of the local CONTEXT should also be made explicit to participating partners before starting any exercise on reflexive collaboration, including teachers, students, and service users.

Guiding questions:

|

|

Here are three examples of how to put the RPP principles into practice. The first example demonstrates how to develop a social and health RPP with a client with chronic pain. The second example showcases how teachers and students in Ireland worked together to develop a course with women in recovery from addiction. Lastly, the third example discusses participative research practices in Belgium.

7. Putting RPP principles into social and healthcare practice

During the project, interesting activities and case studies from the field practice in the participating countries were presented and discussed. For example, the concept of co-production from Great Britain (The Social Care Institute for Excellence) and its application in mental health care was presented (link to resources on Co-production). Co-production means, according to this resource, that people with different views and ideas come together with the aim of improving a situation to everybody's benefit. This concept was related to better social and health services provision. Some participants related it to their experience with community groups (e.g., older people living in a specific community in Portugal, Travellers in Ireland, Roma people in the Czech Republic) or in fieldwork using multi-professional networks around specific patients.

We would like to stress again that stating the aim of the partnership is very important. For example, if the implication is to thereby reduce costs of service provision, this can cancel out the declared goal of enhancing the dignity and autonomous decision-making of patients in such initiatives (link to material on co-production) because it shifts the burden of the service provision to family members and self-help groups of frail people. Negotiating and balancing different MOTIVATIONS behind the proclaimed partnership is therefore crucial.

Another important consideration concerns status differences (power of expertise, position and knowledge) not only between professionals and non-professionals but also between different professional groups (social workers, nurses, medical doctors, physiotherapists etc.). These differences are real and need to be addressed (in the PPR packages CONTEXT + OWN POSITION + HOW I SEE THE PARTNERS). Every profession and professional position have a specific status in society. During their education, the students are usually led to develop their professional identity and to be proud of themselves as professionals.

|

How do your professional identity and position influence your sense of worth in society and as a human being? What aspects of your role as a Social Worker, Nurse, Physiotherapist, Teacher, or Researcher make you proud? |

Differences in status do not only concern professions but also human abilities and attributes. People move in and identify with different networks and social "bubbles". Comparing oneself to others and aiming for positive feedback, belonging to specific networks and reaching higher status in a group or network (for instance, by getting more "likes") indicates a permanent but subtle struggle to stand out. This can cause invisible barriers in collaborative partnerships. It is not constructive to deny or neglect the many differences among people.

|

What are you proud of as a person? |

It is well-known in teamwork theory that the most efficient teams that have diverse members. However, the composition of the team must contain certain abilities which enable the team to fulfil its tasks. When we think about the participation of certain members in a community partnership, for example, professionals and service users, we do not want to negate some members' professional expertise or management abilities and skills. Instead, we should recognize and value them. Likewise, we should appreciate the "experts by experience" as valuable members. All members of the partnership should contribute to the common goal by offering their specific expertise without dismissing the expertise of others.

Tensions may arise in finding the right balance of risk and responsibility in collaborating with people with mental illness or dementia or another type of service user considered a risk. For example, trying to understand the desires and preferences of people with dementia can get tricky when they seem to make an "unwise decision" or when their choices differ from those of their family caregiver (especially when they rely on their family member's support to follow through with the decision). Without learning to trust that taking such risks brings more good than harm, it's hard to challenge our own expectations and assumptions about what seems "wise" to us.

Peer advocacy groups in a range of educational, research and practice contexts can be forms of collaboration that bring a greater balance of power and influence. This has been developed as a recognized form of self-representation by service user groups, and these groups can effectively build relationships with academics, students, practitioners, and researchers. They reduce the risk of participation in teaching and research becoming tokenistic. The following set of principles and processes, used by the Irish Advocacy Network (www.irishadvocacynetwork.com) in the context of mental health, is such an example that could be modified for different country contexts (link to O2).

Building a realistic, reflexive-participative partnership in the field means considering all mentioned problems concerning differences in status and knowledge. Removing barriers in the form of hidden agendas and false preconceptions is a long-term process based on openness and reflexivity. To encourage those who would like to start their own exercise, we present an example by a supervision student. He has a professional background as a physiotherapist and started to think about how to help his client with chronic illness with the support of the RPP scheme. This is not a "best practice" example but shares Jarda's starting point in RPP in his situated practice.

Here is the example of supporting network around the patient with chronic illness.

8. Putting RPP principles into educational practice

Educational practice in social work is important, particularly for developing positive attitudes to reflexivity and participation based on experience. Education that raises interest in "otherness" generally, and specifically in minority groups, makes an important contribution to advanced social work practice. The following are examples collected during the project. The reader can find many others in the outcomes O2 and O3.

Choosing a setting

Each process of RPP takes place in a concrete setting and space, whether an educational setting or its neighbourhood, in the community, or concrete social or health services. The appropriate setting can help to overcome barriers and stereotypes related often to the school environment (link to Example of innovative practice (Belgium):

One way or the other, when service users and/or providers, students and teachers are involved in educational settings, it should be in an open, safe setting, which need not always be in the classroom. Further inspirations of alternative settings mentioned during the project can be found in this link (Settings in educational practice).

It is often difficult to understand issues of representation and working in partnerships authentically. We need to demonstrate commitment to genuine empowerment that can lead to long-lasting student learning (Tanner et al., 2017). If social work educators perform their roles as facilitators and partners inadequately, then students, even those keen to address issues of power and discrimination, will be hindered in their learning.

To remove such obstacles, there is a need to systemically create meaningful opportunities for change that improve the profession's understanding of the lives of service users. These can lead to mutual learning and empowerment for service users and students. Several models have been suggested that demonstrate ways in which tensions and challenges can be resolved (SCIE, 2004)

References:

Involving service users and carers in social work education – Thinking about the meaning and level of involvement (scie.org.uk)

Tanner, D., Littlechild, R., Duffy, J., & Hayes, D. (2017). ‘Making it real’: evaluating the impact of service user and carer involvement in social work education. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(2), 467–486.

Confronting issues of power

It is tempting to think of teaching social work to students as a technicality: "If you know and understand educational principles, then there can be good learning outcomes ". However, this rather simplistic approach will rarely be effective for introducing service user empowerment. From the outset, a more authentic and purposeful approach is to explore your inner world and how you have processed your personal and professional experiences regarding family life, interests in social justice and reasons for engagement with particular, disadvantaged groups.

Academics and professionals teaching social work students must consider these identity questions and general social attitudes in these engagements. Of crucial concern are issues of power in the development of these relationships. It is generally the case that academics and professionals are more powerful than students and service users. Historically they have created and recreated the language used to describe problems and interventions; conversely, service users and students are relatively powerless in influencing the knowledge base, language and decision-making processes.

This is a core issue that has to be addressed from the outset of the engagement. Imbalances of power should be explained and understood fully, and present and future obstacles to learning and action should be identified and challenged. For example, this might include clarity about the use of language, the creation of spaces for debate and resolution of conflicts, and agreement about levels of involvement in planning, delivery and assessment of learning.

References:

Why intersectionality matters for social work practice in adult services – Social work with adults (blog.gov.uk)

Charter, M.L. (2021). "Exploring the importance of feminist identity in social work education." Journal of Teaching in Social Work 41, no. 2 (2021): 117–134.

There are no easy ways of delivering authentic service user participation in social work education. A crucial beginning point is to find agreement about the collaboration terms, the best outcomes, and how a safe space can be created to allow for positive experiences and learning.

The issue of appropriate ground rules is crucial in this respect:

For instance, all involved in the partnership, including academics, students, and service users, should agree on self-disclosure levels. This could allow for a "pedagogy of discomfort"(Coulter et al., 2013), by which is meant that recognizing and challenging feelings is an essential part of experiential learning but needs to be kept within safe boundaries. We suggest explicit statements about

- rules of confidentiality,

- speaking for oneself and not for others,

- owning one's experiences,

- understanding the affective as well as the cognitive content of encounters,

- ensuring that everyone involved understands the principles of duty to care.

It is likely that, even when such principles are operationalized, there will be moments when conflicts become problematic and sometimes hard to resolve. This requires processes of safe conflict resolution and opportunities for debriefing.

| Try to reflect and explore concrete situations and strategies for bringing the partners/group together and starting (continuing) to negotiate the process. |

Link to: Dealing with conflict at work (communitycare.co.uk)

9. Participative research through RPP – Guiding questions

When considering participative research, the first question we must ask is WHY?

|

|

During the development of our project, we engaged in multiple discussions about the barriers and obstacles to service users' participation in research. Overcoming these obstacles paves the way for change and interventions that more deliberately and effectively promote service user empowerment. An inspiration that may come from service users and/or practitioners can provide greater (academic) depth to research topics, such as identifying new aspects of a research question and determining how to address them. Adopting participatory approaches and fostering collaboration can also improve political and ethical accountability, reducing the likelihood that research projects are driven by academic self-interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A fundamental question is: Why and how could service users be supported to become the driving force or/and full partners in the research process, rather than being those who answer the questions or are being 'observed'?

Establishing good relations and credibility as researchers and building trust with potential participants is a precondition for meaningful, authentic research. Bringing service users, service providers, and community representatives together in one research project might create additional challenges and requires a lot of preparatory work and facilitation skills. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the added value of the participative research study.

The possibilities and limitations of service users (and other participants) as research partners need to be clearly articulated for each project. It is essential to maintain constant vigilance regarding the reasons and circumstances for proposing involvement in research, as well as when resistance or failure occurs.

Questions to be considered in joint research:

|

|

Figure 4: Research guiding questions.

Here is an example of participative research using the RPP scheme: link to the Ghent example.

10. GUIDING QUESTION FOR YOUR OWN EXERCISE IN RPP

Finally, we would like to provide you with a format for your own participative exercise or case study. You can use the RPP formula with its guiding questions. Please open it on this link to guiding questions, fill in the results of your reflection and discussion with your colleagues or partners. After finishing it, you can download it as your file and print it on your PC as a plan for Reflexive Participative Partnership.

11. Conclusion

Participation and reflexivity are understood in this Practice Guide as twins because of the complexity of life situations in social work education, practice, and research. These can be enriched by listening to different voices and contributing to fairer organizational, social, and political decisions. A continuous shared reflection on various aspects of who, why, under what conditions and how participation can occur is more likely to lead to good results in reflexive participative partnership.

In this practice guide, we have presented the key ideas, small suggestions and examples of using reflexivity and participation in different contexts of the social and healthcare field. It results from experiences, discussions, and case studies from the international cooperation of five partners - social work universities/schools from representative parts of Europe. Because of our partners' rich variety of historical, socioeconomic, and political backgrounds, we hope the presented RPP scheme and related ideas and proposals can inspire various situations and contexts. You, the readers, teachers, students, practitioners, or community actors, are called upon to look for ways to strengthen participation for shared organizational, social and or political goals.

To those who want to go deeper, we recommend reading the other outcomes of the Erasmus INORP project, which are available at the link to the website and MOOC and its rich references to other resources.

12. References

Adams, R. (2017). Empowerment, participation and social work. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Afrouz, R. (2021). Approaching uncertainty in social work education, a lesson from COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative Social Work, 20(1–2), 561–567.

Arnstein, S. (1969), A Ladder of Citizen Participation, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224.

Bälter O, Hedin B, Tobiasson H, Toivanen S. (2010). Walking Outdoors during Seminars Improved Perceived Seminar Quality and Sense of Well-Being among Participants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Feb 9;15(2):303. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020303. PMID: 29425171; PMCID: PMC5858372.

Beresford, P. (2010). Public partnerships, governance and user involvement: A service user perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 34(5), 495-502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2010.00905.x

Boone, K., Roets, G., & Roose, R. (2019). Raising a critical consciousness in the struggle against poverty: Breaking a culture of silence. Critical Social Policy, 39(3), 434–454.

Brodkin, E. Z. (2021). Street-level organizations at the front lines of crises. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 23(1), 16-29.

Cornwall, A., & Brock, K. (2005). What do buzzwords do for development policy? A critical look at ‘participation’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘poverty reduction’. Third World Quarterly, 26(7), 1043-1060.

Cooke, B., & Kothari, U. (2001). Participation: The new tyranny?. London: Zed Books.

D'Cruz, H., Gillingham, P., & Melendez, S. (2007). Reflexivity, its meanings and relevance for social work: A critical review of the literature. British Journal of Social Work, 37(1), 73–90.

Facer, K., Manners, P., & Agusita, E. (2012). Towards a knowledge base for university- public engagement: Sharing knowledge, building insight, taking action. Bristol: National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement.

Fook, J., White, S., & Gardner, F. (2006). Critical reflection: A review of contemporary literature and understandings. In S. White, J. Fook, & F. Gardner (Eds.), Critical reflection in health and social care (pp. 1–18). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Fung, A. (2006). Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Administration Review 66 (s1), 66–75.

Garland-Thomson, R. (2005). Feminist disability studies. Signs, 30(2), 1557-1587.

Iivonen, S. & Kivipelto, M. (2022) Miten aikuissosiaalityön asiakkaat kokivat saaneensa tarvitsemansa palvelut ja etuudet koronaepidemian aikana? (How did adult social work clients feel they received the services and benefits they needed during the Corona epidemic?) Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare [THL].

Kroll, C., Campbell, J., Donnelly, H., Havrdová, Z., Hradcová, D., Machado, I., Melo, S., Lorenz, W., Povolná, P., Reis, J.A., Roets, G., Roose, R., & Van Beveren, L. (2022). A framework for analysing and reflecting on modes of user participation in social work in a comparative perspective: Conclusions based on analyses of scientific journal articles from the countries participating in the ERASMUS+ INORP-project.

Krumer-Nevo, M. (2005). Listening to ‘life knowledge’: A new research direction in poverty studies. International Journal of Social Welfare, 14(2), 99-106.

Krumer-Nevo, M. (2008). From noise to voice: How social work can benefit from the knowledge of people in poverty. International Social Work, 51(4), 556-565.

Locock, L., O'Donnell, D., Donnelly, S., Ellis, L., Kroll, T., Ní Shé, E., & Ryan, S. (2022) ‘Language has been granted too much power’. Challenging the power of words with time and flexibility in the recommencements stage of research involving those with cognitive impairment. Health Expectations, 25, 2609-2613.

Loughran, H., & Broderick, G. (2017). From service-user to social work examiner: Not a bridge too far. Social Work Education, 36(2), 188-202. doi:10.1080/02615479.2016.1268592

Malacrida, C. (2007). Negotiating the dependency/nurturance tightrope: Dilemmas of motherhood and disability. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 44(4), 469-493.

Malacrida, C. (2009). Performing motherhood in a disablist world: Dilemmas of motherhood, femininity and disability. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22(1), 99-117.

Marres, N. (2005). “Issues Spark a Public into Being: A Key but Often Forgotten Point of the Lippmann-Dewey Debate.” In Making Things Public. MIT Press.

Ní Shé, É., Morton, S., Lambert, V., Ní Cheallaigh, C., Lacey, V., Dunn, E., ... & Kroll, T. (2019). Clarifying the mechanisms and resources that enable the reciprocal involvement of seldom heard groups in health and social care research: A collaborative rapid realist review process. Health Expectations, 22(3), 298-306.

Roets, G., Roose, R., De Bie, M., Claes, L., & Van Hove, G. (2012). Pawns or pioneers? The logic of user participation in anti-poverty policy making in public policy units in Belgium, Social Policy & Administration, 46(7), 807–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00847

Roose, R., Roets, G., & Bouverne-De Bie, M. (2012). Irony and social work: In search of the happy Sisyphus. British Journal of Social Work, 42(8), 1592-1607.

Rosanvallon, P. (2011). Democratic Legitimacy. In Democratic Legitimacy (Issue February 2021, pp. 1–12). https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691149486.001.0001

Social Workers Registration Board (2022). Criteria for Education and Training Programmes: Guidelines for Program Providers, Dublin.

Van Beveren, L., Roets, G., Buysse, A., & Rutten, K. (2022). ‘Enjoy poverty’: Introducing a rhetorical approach to critical reflection and reflexivity in social work education. European Journal of Social Work, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2022.2063807