Reflexivity and participation in communities CZ

10. Module sections

10.4. Section 4: The RPP Model applied to participative research

Aim: in this section PhD candidates will critically examine the opportunities and obstacles encountered in putting together and implementing a participative research project. In correspondence with the cyclical nature of the model this process will have to be repeated at regular intervals in relation to the planning and implementation process.

This part of the module requires the direct involvement of the academic supervisors of each thesis in the planning and timing of each presentation.

Service user group representatives who are partners of the respective research topic and project play a partner role in accordance with the principles and guidelines for participative professional learning outlined in the Guide Book.

Since the topics constitute “packages” in a circular arrangement, the sequence in which they are being addressed allows for flexibility and for repetitions.

For background and implications for participative learning and practice approaches see the section in the Practice Guide.

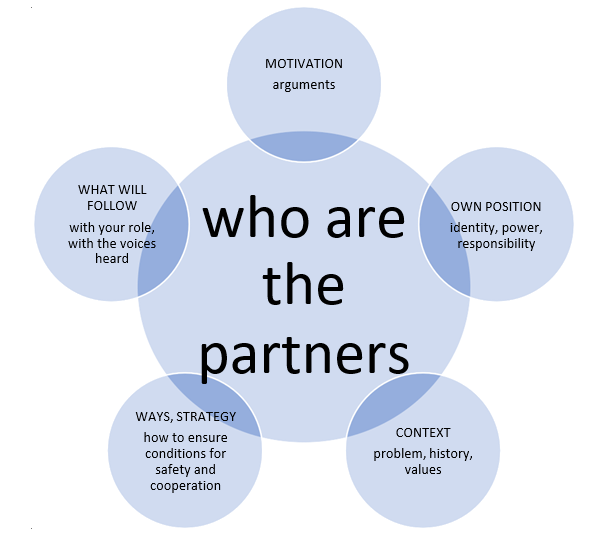

| Package | Topics | Guiding questions |

| Motivation |

Intellectual pathways leading up to the topic choice Biographical motivation and corresponding experiences Political and ethical principles that will be “tested” by the proposed research topic |

Which parts and themes of my previous studies connect me to this research topic? Can I translate my personal motives into motives that To what extent am I prepared |

| Partners |

In most cases of practice-relevant research access to service user groups will be Finding partners at both levels requires considerations of |

Which service agencies can best mediate access to user groups? Can the involvement of agencies and professionals What is “typical”, what is probably person-specific about the life experience of a service user? |

| Context |

The actuality of the proposed research topic in academic discourses nationally and internationally The actuality (or lack of) of the proposed research topic in current political debates nationally and internationally Origins of the research interest (funding programme / agency, service agency, user group commission, own commission …) Research funding conditions as expressions of a political agenda |

In which academic contexts is the topic being discussed? To what extent are the academic discourses based on participative research? What are the links between academic and political interests in the topic? Can the funding conditions for research topic affect the political treatment of the topic? |

| Own position |

Participative approaches as part of the research funding conditions and their Issues of power differentials – risk of academics determining “the agenda” for practitioners and for service users and ways of addressing this risk Distinguishing own expectations from those of other partners – issue of “raising Own position in the scientific community |

How can I avoid that the participative approach may be perceived by service users as “tokenism”? To what extent can I relativise my power position as an academic and in what way can power differentials be Does my proposal raise expectations among service users which cannot be fulfilled? What are the implications of choosing a participative approach for my career |

| Research strategies |

Examination of participative research Status of research as “independent” or “contractual” Boundaries of confidentiality and privacy |

What are the strengths and Do my research strategies allow me to distance myself from the agendas of the partners? How do confidentiality conditions impact my research |

| Expected implications of results |

Modes of presenting results (causal explanations, descriptive phenomena, shared narratives …) “Ownership” of research findings – whose benefit? Dealing with unexpected results Modes of dissemination |

Who and what determines the mode of presenting my How can “benefits” arising from findings be shared? How do I prepare for findings that might render partners (more) vulnerable? |

Resources:

Cancian, F. (1993). Conflicts between activist research and academic success: Participatory research and alternative strategies. American Sociologist, 24(1), 92–106.

Cornwall, A. (2008) ‘Unpacking “participation”: models, meanings and practices’, Community Development Journal, 43(3): 269–83.

Dodson, L., Piatelli, D., & Schmalzbauer, L. (2007). Researching inequality through interpretive collaborations: Shifting power and the unspoken contract. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(6), 821–843.

MacFarlane, A., Galvin, R-, O'Sullivan, M., McInerney, C., Meagher, E., Burke, D. and LeMaster, J. W.. (2017). Participatory Methods for Research Prioritization in Primary Care: An Analysis of the World Café Approach in Ireland and the USA. Family Practice, 34 (3), 278-84.

Malka, M., & Moshe-Grodofsky, M. (2021). Social-work students’ perspectives on their learning process following the implementation of community based participatory research in a community practice course. Social Work Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1989398

Pain, R., Kindon, S., & Kesby, M. (2007). Participatory action research: Making a difference to theory, practice and action. In S. Kindon, R. Pain, & M. Kesby (Eds.), Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp. 26–32). Abingdon: Routledge.

Van Der Vaart, G., Van Hoven, B. and. Huigen, P. P. P. (2018). Creative and Arts-based Research

Methods in Academic Research. Lessons from a Participatory Research Project in the Netherlands. Forum, Qualitative Social Research, 19 (2)

Practice example: See Practice Guide “The participation of families in poverty situations in research on child and family social work: learning from a Belgian social work research project”