Curriculum „Enhancing participative practice in social work”

| Site: | MOOC Charles University |

| Course: | Reflexivity and participation in communities CZ |

| Book: | Curriculum „Enhancing participative practice in social work” |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 17 February 2026, 7:20 PM |

Description

Table of contents

- 1. Output 5

- 2. Preamble

- 3. Level 1: Basic academic level (1st cycle) module

- 3.1. Lesson 1 (2 hours): preparatory considerations – social work theory context

- 3.2. Lesson 2 (2 hours) preparatory considerations – the personal context

- 3.3. Lesson 3 (4 hours): Conceptual clarifications 1: Reflectivity

- 3.4. Lesson 4 (3 hours): Conceptual clarifications 2: Political contexts of participation

- 3.5. Lesson 5 (3 hours): Preparing for participative learning experiences

- 3.6. Lesson 6 (6 hours): Transferring reflective participative learning principles to participative practice contexts

- 4. Preparation for intervention

- 5. Competence perspective

- 6. Post-graduate module suggestions (2nd cycle)

- 7. 2nd cycle Competence levels according to the Dublin Descriptors

- 8. Participation in research (3rd cycle)

- 9. Didactic considerations

- 10. Module sections

- 11. 3rd cycle Competence levels according to the Dublin Descriptors

1. Output 5

Curriculum „Enhancing participative practice in social work”

Intellectual Output 5 INORP

This output has been developed as part of the INORP project, Innovation by supporting reflexivity and participation: Strengthening education and professionalization of social work on the border of other professions, co-financed by EU funds under the Erasmus+ K203-CAC1B7D2 strategic partnership for innovation for the period 2020-2023. The project partners include:

- Charles University (Czech Republic) as Project Coordinator;

- Ghent University (Belgium);

- Helsingin Yliopisto (Finland);

- University College Dublin (Ireland);

- Cooperativa De Ensino Superior De Serviço Social (Portugal)- leading organization of this output (Walter Lorenz and others).

The Association of Educators in Social Work (ASVSP) is an associate partner.

2. Preamble

These model proposals aim to develop a critical and differentiated understanding of and competence in participative approaches to learning, practice and research in the social professions. This is supported by an emphasis on reflectivity throughout by means of guiding questions. Reflective abilities are an essential competence for accountable professional practice (but are not the explicit objective of this curriculum). As a criterion for defining and clarifying the purpose of participatory approaches to practice and learning they correspond to the fluidity and flexibility intended in this proposal since participation cannot be learned according to standardised rules. Reflectivity is a skill for monitoring the effects the exposure to the material and the encounters with service users have on the learners and their learning processes. Reflectivity is to be treated not primarily as an individualised activity but as a dialogical process whereby knowledge, experience and assumptions can be explored openly without the pressure of thereby finding “the definitive approach”. The aim of the programme is therefore to explore the margins of both reflectivity and participation in an interactive context and approach.

This requires explicit attention to processes of trust-building among teachers and learners, learners among themselves, service users and academic institutions.

The guiding principles underlying this proposal are contained in the accompanying “Practice Guide”- Output 4 INORP.

3. Level 1: Basic academic level (1st cycle) module

3.1. Lesson 1 (2 hours): preparatory considerations – social work theory context

3.2. Lesson 2 (2 hours) preparatory considerations – the personal context

3.3. Lesson 3 (4 hours): Conceptual clarifications 1: Reflectivity

3.4. Lesson 4 (3 hours): Conceptual clarifications 2: Political contexts of participation

3.5. Lesson 5 (3 hours): Preparing for participative learning experiences

3.1. Lesson 1 (2 hours): preparatory considerations – social work theory context

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

|

Professional core |

Reasserting professional principles of social work Social work aims at achieving changes in people’s lives chiefly through their consensual participation in the required processes. Therefore, participation in practice is not an optional extra that applies only to selected situations but a fundamental Global Definition of the Social Work Profession „Social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledges, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing. The above definition may be amplified at national and/or regional levels.” (IFSW, 2014). |

What constitutes the dignity of a person? What factors can limit the capacity of a person to be self-determined? In what sense does the |

| Epistemology |

“Diagnosis” between “objectivity and subjectivity” The discussion on “subjectivity and objectivity” is misleading; instead, authors use the term “lived experience for the direct experience of the world which orientates a person’s self-conception and around which individuals organise their lives. This position is central, since it differs from an Consequences: |

List some factors which are used to define your identity “factually” (gender, age, passport etc.) – do they define their meaning for you? When did hearing a service user’s description of a problem fall outside your own “lived experience”? What emotional reactions did that trigger in you? |

| Ethics |

Participation requires ethical considerations Bridging the divide between different worlds of meaning poses a considerable challenge and implies potential for conflict, misunderstandings and mistakes because it inevitably exposes status and power differentials of various kinds. To safeguard all participants and to respect the vulnerability implied on all parts ethical standards need to be applied explicitly to all transactions so as to set acceptable limits to the extent to which personal details can be shared, emotions can be made subjects of learning and expectations for certain outcomes can be raised. |

Consult the Code of Ethics for the social work profession in your country – which principles are most relevant for participatory approaches? Where do you anticipate conflicts of interest |

Resources:

Afrouz, R. (2022). Developing inclusive, diverse and collaborative social work education and practice in Australia. Critical and Radical Social Work, 10 (2). https://doi.org/10.1332/204986021X16553760671786

Banks, S. (2011). Ethics in an age of austerity: Social work and the evolving new public management.

Journal of Social Intervention: Theory and Practice, 20(2), 5–23.

https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.18352/jsi.260

IFSW (International Federation of Social Workers), (2014). Global Definition of Social Work. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

Sheppard, M. (2006). Social Work and Social Exclusion: The Idea of Practice. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315242859

3.2. Lesson 2 (2 hours) preparatory considerations – the personal context

| Theme | Topic | Guiding |

| Motivation |

Social work is a profession that expresses a certain |

What were the basic |

| Awareness |

All action and interaction take place within personal

|

In what situation do I become aware of my “guiding beliefs”? Where do they coincide with |

| Reflection |

Preparation for and accompaniment of participative learning processes must therefore be guided by explicitly organised and guided opportunities for reflection. Learning from reflection can only take place in a non- authoritarian context and relationships that allow also for ambiguity and mistakes to be openly |

What kind of situations make me reflect? |

Resources:

Adams, R. (2008). Empowerment, participation, and social work (4th ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sicora, A. (2017). Reflective Practice, Risk and Mistakes in Social Work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2017.1394823.

*Sterling, J., Jost, J. T. a Hardin, C. D. (2019). Liberal and Conservative Representations of the Good Society: A (Social) Structural Topic Modeling Approach. SAGE Open 9 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019846211

3.3. Lesson 3 (4 hours): Conceptual clarifications 1: Reflectivity

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

| Psychological dimensions |

Reflecting - awareness - thinking Reflecting is an essential and very specifically human capacity. It is linked to the notion of awareness and indicates that human actions are distinguished by individual purpose-giving that is in turn embedded in social and cultural sets of meaning. Research on reflectivity demonstrates the neuro- scientific and psychological necessity of acknowledging the constant influence of pre- conscious conceptual social categories and structures which guide orientation but need to be subjected to processes of awareness in order to make interaction productive and creative. |

What circumstances stimulate my awareness? What is awareness then focused on? |

| Professional dimensions |

The ability to reflecting systematically legitimates professional autonomy AND accountability.

|

Think of any “social problem” you might have |

|

Political |

Reflection and democracy Voting rights in a democracy are granted on the basis that mature citizens can make “rational Citizenship presupposes, but also stimulates, reflective abilities in organising one’s relationship with others. Where these abilities are not (yet) fully developed, pedagogical assistance (not instruction!) is given, Proposal: “Democratic reflectivity” combines - with professional colleagues (in teams, or through professional supervision) |

What kind of considerations guide you on political voting occasions? How can you stimulate reflectivity in learning |

Resources:

*Adams, M. (2003). The reflexive self and culture: A critique. British Journal of Sociology, 54(2), 221– 238. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007131032000080212

*Archer, M. (2012). The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

D’Cruz, H., Gillingham, P. a Melendez, S. (2005). Reflexivity, its Meanings and Relevance for Social Work: A Critical Review of the Literature. British Journal of Social Work, 37(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl001

Dzur, A. W. (2019). Democratic Professionals as Agents of Change. In A.W.Dzur, Democracy Inside: Participatory Innovation in Unlikely Places (pp. 1–24). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190658663.003.0001

Ferguson, H. (2018). How social workers reflect in action and when and why they don’t: the possibilities and limits to reflective practice in social work. Social Work Education, 37(4), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1413083

*Lieberman MD, Gaunt R, Gilbert DT a Trope Y. (2002). Reflection and reflexion: a social cognitive neuroscience approach to attributional inference. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 34:199– 249.

*Phillips, L. (2000). Risk, Reflexivity and Democracy. Nordicom Review, 21(2), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0389.

3.4. Lesson 4 (3 hours): Conceptual clarifications 2: Political contexts of participation

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

| Participation as a right |

Social and civil rights movements and their demands: Social movements (feminism, black empowerment, civil rights, disability rights, gay rights …) criticise In response, international and national legislation opened up new or stronger participation and self- representation rights Examples: “Convention on the Rights of the Child” (UNICEF, https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention) or the UN “Convention on the Rights of Disabled Democracy as an instrument for both inclusion and exclusion? “Grounds for optimism” are the |

Looking back in history, In what areas are you or would you like to become active to campaign for better participation rights? Where would you draw the line and limit public participation rights to |

|

Participation as an |

The neoliberal critique of prioritising citizen rights over citizen obligations. Activation as pre-condition for participation Examples: “In variance to the previous government (in Finland), the government in power from 2011–2015 that continued implementing policies for active citizenship and participation, changed the ideological focal point of Finnish citizenship from social rights and benefits to an obligation to work. This impacted the distribution of citizenship rights and duties in a way that increased inequality”(Matthies, Närhi, & Kokkonen, 2018, 10).

|

How do you perceive your social rights as a citizen of your country – do they Discuss indications of the following phenomena in current political |

| Participation as "consumer choice" |

Privatisation of former public services is being advertised by governments as “giving service users as customers and consumers a wider range of options to choose from”. Trends in the “outsourcing” of social and care services, creation of a “market of services” instead of the “monopoly” of state services create new forms and conditions of participation. “Participation under ideology-determined social policy conditions of neoliberalism becomes “Janus faced… We argue that this type of two-fold participation paradigm deepens the disparity within society, as people dependent on welfare services and in a precarious labour market situation do not benefit from the greater freedoms, and instead have to behave according to the increased expectations |

Can public goods and services be treated like commercial goods and services? What are the likely effects of the emphasis on personal choice for |

|

Risks for a “mechanical” application |

The inflationary, prescribed use of participation can lead to the concept becoming |

In what context does the invitation / condition to practice participation arise? What is the declared and what is the hidden agenda of a programme that |

Resources:

Beresford, P. (2010). Public partnerships, governance and user involvement: A service user perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 34(5), 495-502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2010.00905.x

Boone, K., Roets, G. a Roose, R. (2019). Raising a critical consciousness in the struggle against poverty: Breaking a culture of silence. Critical Social Policy, 39(3), 434–454.

Cornwall, A. a Brock, K. (2005). What do buzzwords do for development policy? A critical look at ‘participation’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘poverty reduction’. Third World Quarterly, 26(7), 1043-1060.

*della Porta, D. (2022). Progressive Social Movements and the Creation of European Public Spheres. Theory, Culture and Society, 39 (4). https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764221103510

Handler, J. F. (2005). Workfare Work: The Impact of Workfare on the Worker / Client Relationship. Social Work 3 (2), 174–181.

Matthies, A.-L., Närhi, K. a Kokkonen, T. (2018). The Promise and Deception of Participation in Welfare Services for Unemployed Young People. Critical Social Work, 19(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.22329/csw.v19i2.5677

Roets, G., Roose, R., De Bie, M., Claes, L. a Van Hove, G. (2012). Pawns or pioneers? The logic of user participation in anti-poverty policy making in public policy units in Belgium, Social Policy & Administration, 46(7), 807–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00847

*Rosanvallon, P. (2011). The Metamorphoses of Democratic Legitimacy: Impartiality, Reflexivity, Proximity. Constellations 18 (2), 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.2011.00631.x

Taylor-Gooby, P. (1989). The politics of welfare privatization: The British experience. International Journal of Health Services 19 (2). https://doi.org/10.2190/NGX2-3YK9-CRKU-P4T3

*Tronto, J.C. (2013): Caring Democracy. Markets, Equality, and Justice. New York University Press.

Watson, S. (2015). Does welfare conditionality reduce democratic participation? Comparative Political Studies, 48 (5), 645–686.

3.5. Lesson 5 (3 hours): Preparing for participative learning experiences

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

| Establishing partnership with a user group |

In many countries, it is now a requirement that users of social services become engaged in teaching the social work curriculum. Pre-contact considerations: - recourse to pre-existing contacts (through placements, academics involved in service agencies, participative research projects) - clarification of “representation” (do user groups select speakers or does the academic side make direct contacts; speaking for themselves or on behalf of a group - safeguarding vulnerability: engagements must be voluntary, contractual arrangements concerning confidentiality; boundary setting and offers of emotional and financial support for participation - topics and objectives of presentations need to be clearly defined beforehand and if needed re-negotiated explicitly in the process. |

What do I expect to learn from the direct encounter with accounts of experiences by service users? What are they expecting to gain from the encounter? What is the shared context that “frames” the |

|

Opportunities for shared learning |

Listening to “authentic voices” of “lived The unexpected is likely to be controversial, one- sided, in conflict with “standard opinion”. Choosing a secure setting is vital (preparation of a comfortable arrangement of a seminar room, It requires, but also contributes to, an inclusive atmosphere in which differences of background, identity and power do not disappear (caution: “prescribed tolerance” can invalidate the encounter!) but can be openly acknowledged. Learning aims at distinguishing between legitimate and imposed boundaries and differences and at negotiating mutually acceptable meanings given to those differences. |

What did I expect to hear from the presenters? Which kind of environment communicates a sense of safety to the participants? How can I constructively deal with strong emotions, in myself and in others? Which parts of the |

| Pitfalls and risks |

Service users as presenters of their knowledge might not have any experience in sharing it with Presenters are very dependent on authentic Divergences of interest between different presenters might arise during a session. Service users may have experiences of hostility against their “voice” in a public context and |

How can I express “active listening”? With what kind of reactions can I facilitate the learning opportunities of the What are the indicators of “genuine appreciation”? |

Resources:

Viz zdroj INORP, výstup 4: Model RPP:

Driessens, K. a Lyssens-Danneboom, Vicky, editor. (2022). Involving Service Users in Social Work Education, Research and Policy : A Comparative European Analysis.Bristol: Bristol University Press

*Goh, E. C. L. (2012). Integrating Mindfulness and Reflection in the Teaching and Learning of Listening Skills for Undergraduate Social Work Students in Singapore. Social Work Education, 31(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2011.579094

Rogers, A. a Welch, B. (2009). Using standardized clients in the classroom: An evaluation of a training module to teach active listening skills to social work students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 29 (2). https://doi.org/10.1080/08841230802238203

Schiettecat, T., Roets, G., Vandenbroeck, M. (2018). Capturing life histories about movements into and out of poverty: A road with pits and bumps. Qualitative Social Work, 17(3), 387-404.

Spector-Mersel, G. (2017). Life Story Reflection in Social Work Education: A Practical Model. Journal of Social Work Education, 53 (2). https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1243498

3.6. Lesson 6 (6 hours): Transferring reflective participative learning principles to participative practice contexts

General preparation:

Learning from interactive practice experiences is strongly aided by learning “tools” that support the reflective dimension of “learning from experience”.

| Tools aiding the learning process of students |

- Reflective diaries (the dynamic transfer of non-linear impressions, - “Context sampling” (photography, audio-recording, representative objects etc. can amplify the memorisation of incidents and impressions and provide material for the “re-creation” of practice situations under - “critical incidents” (the re-construction from memory of situations that posed specific challenges and the considerations that were examined as options for intervention, as well as their theoretical and methodological |

|

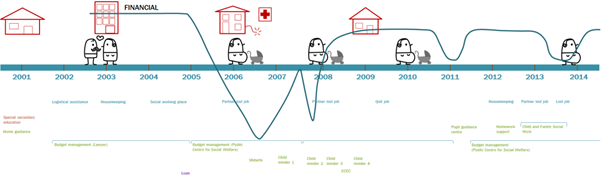

Tools aiding |

- Life story graphs (templates for the sequential visualisation of significant life events in response to critical context changes; see example below and context in case illustration on INORP output 4, case example Ghent) - Photography, sketching, audio-recording (handing appropriate recording gadgets for autonomous use to service users can collect material under their control. Discussions on the product allow them to attribute their personal - Story boards (specially for children, adults with communication difficulties who find it difficult to verbalise impressions, feelings and views, see |

| Digital tools and access to social media |

Digital communication technology is frequently portrayed as automatically enlarging participation opportunities. This may be true in certain cases but professionals must raise the issue of “access justice and equality”. |

Resources:

Storyboard example:

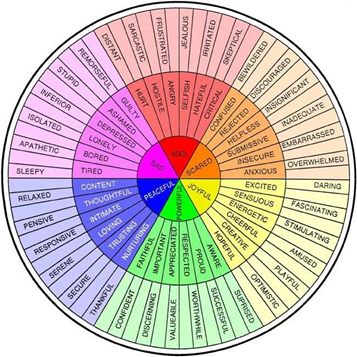

Emotional colour wheel, from “Voice of the child toolkit”

https://www.socialworkerstoolbox.com/voice-child-20-sheets-gain-childs-wishes-feelings-views/

Knei-Paz, C. a Ribner, D.S. (2000). A narrative perspective on “doing” for multiproblem families. Families in Society, 81(5), 475-483.

Schiettecat, T., Roets, G., Vandenbroeck, M. (2018). Capturing life histories about movements into and out of poverty: A road with pits and bumps. Qualitative Social Work, 17(3), 387−404.

4. Preparation for intervention

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

|

Creating |

Participation by service users in finding solutions is not optional but a core condition of professional social work. Meaningful participation arrangements combine the following considerations: Krumer-Nevo & Barak (2007, 37) conclude from |

For what precise purpose is it important to hear and Am I prepared to deal with conflicting versions of “need”? Am I aware of the extent and the limits of my professional power? |

|

Recognising strengths |

Research findings (ibid p. 38): overcoming the “deficit perspective” The collaborative approach assumes that all families have competences (as well as a lack of competences) and are entities which experience to solve problems (e.g. Berg & De Jong, 1996). “Our results demonstrate that if social work aims to support participation and involvement in active citizenship, a genuine respect for service users has to be evident by taking seriously their perspectives, knowledge, and experiences about services” (Matthies, Närhi, & Kokkonen, 2018, 15). |

According to what kind of criteria did I construct my version of “what is the problem”?

|

| Conditions of access | Legal considerations (for instance access to children), “right to be heard” considerations of consent, declaration of intentions, securing confidentiality, “access” needs to be continuously re-negotiated participatively in the process of the exchanges |

Have I checked the legal How do I communicate these? |

| Epistemic rights and boundaries |

epistemic rights: the ‘distribution of rights and responsibilities regarding what participants can |

What are the differences between mine and the service user’s “framing” of the problem? In which circumstances do I make reference to my professional qualifications? What allows me to feel and express sympathy for a service user? |

| Objectives, outcomes |

Outcomes in participative approaches are largely Agreed or contractual premises must therefore include what is to be gained in the process and what are the objectives stated from both sides. Participative approaches aim to make social |

What would for me be the best possible outcome of the intervention? Which are the differences between my and the Does my experiencing “the case” induce me to question the adequacy of existing service provisions or social policies? |

Resources:

Berg, I.K. a De Jong, P. (1996). Solution-building conversations. Co-constructing a sense of competence with clients. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 77(6), 376–391. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.934

Heritage, J. and Raymond, G. (2005). ʻThe terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in talk-in-interactionʼ, Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1): 15–38.

*Huber, M. A., Metze, R., Veldboer, L., Stam, M., van Regenmortel, T. a Abma, T. (2019). The role of a participatory space in the development of citizenship. Journal of Social Intervention: Theory and Practice, 28(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.18352/JSI.583/GALLEY/572/DOWNLOAD

Matthies, A.-L., Närhi, K. a Kokkonen, T. (2018). The Promise and Deception of Participation in Welfare Services for Unemployed Young People. Critical Social Work, 19(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.22329/csw.v19i2.5677

Ribner, D. S. a Knei-Paz, C. (2002). Client's view of a successful helping relationship. Social work, 47(4), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/47.4.379

Saar-Heiman, Y., Lavie-Ajayi, M. a Krumer-Nevo, M. (2017). Poverty-aware social work practice: service users’ perspectives. Child and Family Social Work, 22(2), 1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12325

Sousa L, Costa T. (2010). The multi-professional approach: front-line professionals' behaviours and interactions. International Journal of Social Welfare 19: 444–454.

5. Competence perspective

The material covered to this point constitutes a module to be used at undergraduate (1st cycle) level but can also be used, if students have not yet been exposed to these themes, as introduction to 2nd cycle modules that build on knowledge and competences acquired up to here. Resources relating specifically to the 2nd cycle are marked with asterisk *

Application of Dublin Descriptors to this part of the module:

| 1st cycle | Competences reached by a student | |

| Knowledge and understanding | Based on textbooks and new insights |

Is familiar with core social work principles Understands the importance, but also the |

|

Applying |

Express professional approach through arguments |

Can plan an encounter with a service user group by applying the above knowledge |

| Making judgements |

Gather and interpret relevant data, reflection on relevant social, scientific or ethical issues |

Has examined own values, concepts, feelings, prejudices critically |

| Communication skills |

can communicate |

Has learned to express professional and diagnostic concepts in simple language |

| Learning skills |

Have developed those learning skills that are necessary for them to continue to undertake further study with a high degree of autonomy |

Has developed skills in reflectivity |

6. Post-graduate module suggestions (2nd cycle)

At this level, students should apply previous knowledge and experience to a number of social service contexts which pose particular challenges for participative approaches. The examples can be exchanged for different user groups according to context.

6.1. Example 1: Participation in the context of child welfare and child protection

(to be elaborated in seminar discussions, covering all sections through exercises over a period of 10 hours)

| Theme | Topic and skills | Guiding questions |

| Legal and organisational context |

International level of rights: Nevertheless: national law imposes limitations, e.g. Agency context: |

To what extent does my intervention plan

To what extent does my agency context |

| Format of encounters |

In cases of concerns about child welfare and protection, the following formal scenarios pose challenges to the extent children can be directly Child Protection Conferences: “there is a substantial body of evidence indicating that, despite children’s social care meetings with professionals and families being a key forum for making decisions (Healy and Darlington, 2009), many meetings such as child protection case conferences do not seem to embody or enable principles of self-determination for parents and children. Perhaps because of this, they are often reported to be very difficult for parents and, when they attend, children” (see Hall and Slembrouck, 2001). Cited in Stabler, 2020 p. 30. Family group conferencing is a way of transforming decision making and planning for children into a process led by family members … Children and young people can also be directly involved in their family group conference, usually with the support of an advocate. (ibid) Families here can be given more responsibility for making decisions – and taking Family Team Decision Making / Family Involvement Meetings and joined case planning have been |

What structural, organisational and relational factors may impact the manner in which a child takes To what extent can your role modify the extent of direct participation by |

| Guiding principles |

Prevailing background: Research on children’s experiences and preferences emphasise the following key principles for achieving more positive outcomes: • Collaboration and engagement: before the meeting working with the child/young person so that they are fully prepared for what the meeting is about, what it will look like, what might be shared; during the meeting the child/young person has access to an advocate to support them to take part; after the meeting the child/ young person is offered support that is relevant to their preferences and needs based on people at the meeting having listened to what they had to say. • Building trust and reducing shame: before the meeting the child/ young person is given choices around elements of the meeting, such as where it will be held, who might attend to support them, where everyone should sit; during the meeting the child/young person has some control over how they are involved in the meeting, and are able to leave the room as they need to; after the meeting the process of having participated and shared in a meeting, and having been responded to in a positive way, can build confidence and encourage the child/young person to actively participate in decisions about their lives. • Enabling participation in decision making during the meeting ensuring involvement throughout the meeting, rather than just including children and young people at a point specified for ‘the child’s voice’; |

In what circumstances can participation by

What are the consequences for your preparation for family meetings drawn from research findings? Can you suggest |

Resources:

Ashley, C., Holton, L., Horan, H. & Wiffin, J. (2006) The Family Group Conference Toolkit — a practical guide for setting up and running an FGC service (London, Family Rights Group)

Ashley, C. and Nixon, P. (2007) Family Group Conferences: Where Next? Policies and Practices for the Future. London: Family Rights Group.

Bell, M. (1999) ‘Working in partnership in child protection: the conflicts’, The British Journal of Social Work, 29(3): 437–55.

Bell, M. (2002) ‘Promoting children’s rights through the use of relationship’, Child & Family Social Work, 7(1): 1–11.

Featherstone, B., Morris, K., Daniel, B., Bywaters, P., Brady, G., Bunting, L., Mason, W., & Mirza, N. (2019). Poverty, inequality, child abuse and neglect: Changing the conversation across the UK in child protection? Children and Youth Services Review, 97, 127-133 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.009

Godar, R. (2015) ‘The hallmarks of effective participation: evidencing the voice of the child’, in M. Ivory (ed.), The Voice of the Child: Evidence Review. Dartington: Research in Practice, pp 10–21. https://www.researchinpractice.org.uk/children/publications/2015/december/voice-of-the-child- evidence-review-2015/

Hall, C. and Slembrouck, S. (2001) ‘Parent participation in social work meetings – the case of child protection conferences’, European Journal of Social Work, 4(2): 143–60.

Hartas, D. and Lindsay, G. (2011). ‘Young people’s involvement in service evaluation and decision making’. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 16(2): 129–43.

Marsh, P. and Crow, G .(1998). Family Group Conferences in Child Welfare. Oxford: Blackwell

Stabler, L. (2020). Children’s and parents’ participation: current thinking. In: C. Diaz (ed.). Decision Making in Child and Family Social Work. Perspectives on Children’s Participation (pp. 2-41). Bristol: Policy Press.

Tang, C. (2006) Developmentally sensitive interviewing of pre-school children: some guidelines drawing from basic psychological research. Criminal Justice Review, 31, 132– 14

Willow, C., Marchant, R., Kirby, P. & Neale, B. (2004) Young Children's Citizenship. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, London.

6.2. Example 2: Participation in the context of disability services

(to be elaborated in seminar discussions, covering all sections through exercises over a period of 10 hours)

| Theme | Topic and skills | Guiding questions |

|

Basic and specific |

Consideration to the international and national legal framework of the rights of people with Practical consequences for social work of regarding Importance of the social model of disability: “the subjective meanings individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) attribute to their own lives, their dreams and their aspirations continue, in many cases, are being ignored” (Neuman, 2020) Critical questions regarding participation and disability: Participation needs to be conceptualised and applied as fluid and multifaceted: |

What direct experiences of encounters with people with disability do I have? To what extent can I consider my own abilities to be limited? What are the main factors why people with disability are not In which areas did people with disability gain |

|

Priorities set by people with disability |

Study of research findings 1. Self-determination: “participation was not only framed as ‘success’, ‘independence’ or ‘fulfilment’, as contemporary discourses may 2. Inclusive environments: “Research draws attention to the importance of shifting responsibility for inclusive practices to society, rather than onto the individual. Yet, despite this need for a societal solution, some research participants held an individual responsibility for their integration”. (ibid., 56) 3. Identity integration / intersectionality: “Participants alluded to at least three identity postures grounded in the connexion of ageing and disability: that of older citizens who are equal to others, that of long-term activists struggling for social justice and that of persons who are living the tensions between ageing and ageing with a disability” (ibid. 57). |

Which of these priorities set by people with disability coincide with core social work principles, which go beyond them? How do you understand intersectionality and the importance of identity policies in relation to disability? |

| Collaborative intervention strategies |

The social model of disability: focused on the critique of oppressive practices The rights approach stresses the role of legal instruments in protecting the well-being of people with disabilities The developmental approach is associated with the integration of people with disabilities into the social and economic life of the community and goes beyond offering “individualised solutions” The participative turn: The rights-based, developmental approach 1. emphasizes the leadership of people with disabilities and their organizations in campaigning for rights, services, and opportunities. It also recognizes their right to self determination and to be protected against discrimination., 2. a rights-based, developmental approach places emphasis on community living and seeks to normalize living arrangements of people with disabilities. 3. To promote economic and social integration, it requires social investments that ensure the acquisition of educational qualifications and skills that facilitate the full participation of people with disabilities in the productive economy. (Knapp & Midgley, 2010, 94) The ”Dare to Dream” Project (Neuman, & Bryen, 2022). See below |

How do you understand the interaction of the “material” and the “constructed” aspects of disability in your approach to Beyond which threshold does the application of a “rights approach” problematic in relation to work with people with disabilities) |

Resources:

Raymond, É., Grenier, A., & Hanley, J. (2014). Community participation of older adults with disabilities. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 24(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2173

Beresford, P. (1999) 'Making participation possible: Movements of disabled people and psychiatric survivors', in Jordan, T. and Lent, A., (Eds.). Storming The Millennium, London: Lawrence and Wishart (pp. 35-50).

Beresford, P. (2000). Service users’ knowledges and social work theory: Conflict or collaboration? British Journal of Social Work, 30(4), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/30.4.489

Croft, S. and Beresford, P. (1996). 'The politics of participation', in Taylor, D. (ed.), Critical Social Policy: A Reader, London: Sage, pp. 175-198

Ellcessor, E. (2016). Restricted Access: Media, Disability, and the Politics of Participation. New York, USA: New York University Press.

Knapp, Jennifer, & James Midgley, (2010); 'Developmental Social Work and People with Disabilities',

in James Midgley, and Amy Conley (eds), Social Work and Social Development: Theories and Skills for Developmental Social Work (New York, online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 May 2010), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199732326.003.0005

Neuman, R., & Bryen, D. N. (2022). Dare to Dream: The Changing Role of Social Work in Supporting Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. British Journal of Social Work, 52(5), 2613– 2632. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab195

Neuman, R. (2020). ‘The life journeys of adults with intellectual and developmental Disabilities: Implications for a new model of holistic supports’, Journal of Social Service Research, 1–16. 10.1080/01488376.2020.1802396.

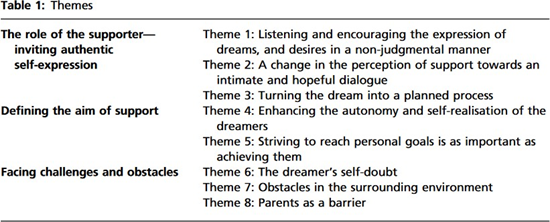

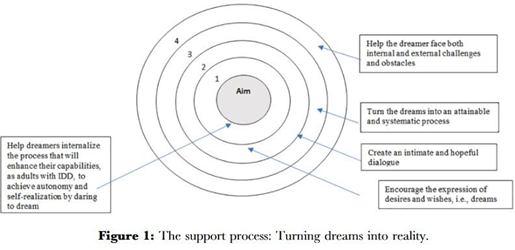

The ”Dare to Dream” Project (Neuman, & Bryen, 2022, 2622).

The ”Dare to Dream” Project (Neuman, & Bryen, 2022, 2626).

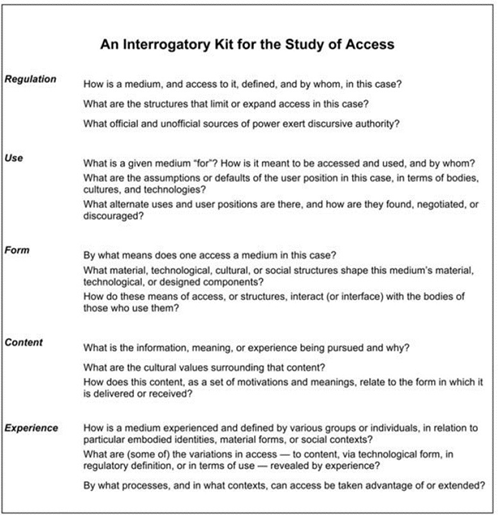

The ”Access Kit” (Ellcessor, 2016, p. 19).

7. 2nd cycle Competence levels according to the Dublin Descriptors

| 2nd cycle | competences | |

| Knowledge and understanding | Shows originality with research orientation |

In view of the complexity of the sample issues students have acquired knowledge and understanding that goes questions |

| Applying knowledge and understanding | Applies knowledge to unfamiliar areas, multidisciplinary |

Each of the sample areas contain a multiplicity of intersectional factors; students are able to priorities and combine knowledge situation- specifically to negotiate and act upon the needs articulated by service users professionally and accountably |

| Making judgements |

Integrate knowledge and handle complexity, reflecting on social and ethical responsibilities linked to the application of their knowledge and judgements |

Students have learned to make judgements and decisions on intervention strategies by way of integrating ethical, scientific, political and psychological considerations flexibly but according to transparent presentation of evidence |

| Communication skills |

can communicate their conclusions, and the knowledge and rationale under pinning these, to specialist and non specialist audiences clearly and unambiguously |

Graduates have practised their communication skills in a variety of very different contexts (student seminars, scientific debates, meetings with user groups, discussions with community representatives and policy makers) |

| Learning skills | Self-directed learning |

Students are aware of the extent and the limitations of the specialised knowledge acquired in the course of this programme and are motivated to continue applying reflective learning skills in their professional practice. |

8. Participation in research (3rd cycle)

8.1. Preamble

Participation as part of a curriculum at the academic 3rd cycle level is expressed as learning

competences in participative research. In a very basic sense all research in the field of social work

that involves direct contact with service users contains elements of participation. Nevertheless, the following proposals are aimed at strengthening the participative dimension of such research in order to give such research additional quality characteristics, such as

- Giving participants the right to have their voice heard through research

- Expressing an ethical commitment to treating “informants” not as objects but as subjects and thereby safeguarding their dignity

- Strengthening the practice impact of research through the involvement of partners and service users in the implementation of findings and by effecting policy changes. (Banks et al., 2013)

There is no one overall model of participatory research. Instead the following proposals for curriculum contents are intended to stimulate a variety of approaches appropriate to each research project and research context in PhD studies and beyond.

Access to this module presupposes participation in key elements of the curriculum proposals relevant to the 1st and 2nd cycle concerning participative practice in social work.

These elements concern the following module themes:

Personal dimensions of the researcher as a professional

- Motivation

- Awareness

- Reflectivity

Principles and practices of reflecting

- Psychological aspects

- Professional aspects

- Political aspects

Political context of participation

- Citizenship rights and obligations

- Participation and consumerism

9. Didactic considerations

Sections 1-3 take the form of whole day (8 hours) group discussions for which PhD candidates prepare presentations on key texts and documents from the “resources” list (or beyond) to which they take position from different perspectives.

Section 4 takes the form of periodic presentations by PhD candidates in which they report on the current state of their preparation for and management of their research project according to the then relevant items of the RPP Model. Each presentation will be subjected to group reflections in which experiences and insights, difficulties and solutions are being exchanged.

10.1. Section 1: Background, principles and context of participative research approaches

Aim: To familiarise PhD candidates with the wider conceptual and political context in which participative research approaches are located, their potential and difficulties in realisation

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

|

Research traditions |

Objectivity and subjectivity in human science research Epistemology between positivism and post- modern relativism Contexts and interpretations of “Evidence Based Practice” |

What reasons justify researcher objectivity? How can detachment and neutrality prevent you from obtaining meaningful insights into your research topic? What counts for you as |

| Challenges in social work research |

Types and pragmatics of research partnerships in view of limitations imposed by |

What could be undesirable outcomes of my research project? Which criteria distinguish desirable from undesirable research outcomes? |

|

Forms and levels of |

- Community-controlled and -managed, no professional researchers involved. – Advisory group involved in research design or dissemination. Proposal: “Democratic partnership” |

What is the intended level of community / user involvement in your research project?

What kind of practical |

Resources:

Burdon, P. D. (2015). Hannah Arendt: On Judgment and Responsibility. Griffith Law Review, 24 (2), pp. 221–243.

D'Cruz, H., & Jones, M. (2004). Three different ways of knowing and their relevance for research. SAGE Publications Ltd, https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857024640

Fleming, J., Beresford, P., Bewley, C., Croft, S., Branfield, F., Postle, K. and Turner, M. (2014) ‘Working together: innovative collaboration in social care research’, Qualitative Social Work, 13(5): 706–22.

Healy, K., Darlington, Y. & Yellowlees, J. (2011) Family participation in child protection practice: an observational study of family group meetings. Child & Family Social Work, 17 (1),1–12.

Krumer-Nevo, M. (2008) From ‘noise’ to ‘voice’: how can social work benefit from knowledge of people living in poverty? International Social Work, 51 (4), 556–565.

McCracken, S. G., & Marsh, J. C. (2008). Practitioner expertise in evidence-based practice decision making. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(4), 301–310.

Nolan, M., Hanson, E., Grant, G., Keady, J. and Magnusson, L. (2007) . ‘Introduction: what counts as knowledge; whose knowledge counts? Towards authentic participatory enquiry’, in M. Nolan, E.

Hanson, G. Grant and J. Keady (eds), User Participation in Health and Social Care Research, (pp 1–14) Berkshire: Open University Press.

Reason, P. & Bradbur, H. (Eds.), Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. London: Sage.

Roose, R., Roets, G., Van Houte, S., Vandenhole, W. & Reynaert, D. (2013). From parental

engagement to the engagement of social work services: discussing reductionist and democratic forms of partnership with families. Child & Family Social Work, 18 (4), 449-457.

Ziegler, H. (2020). Social work and the challenge of evidence-based practice. In S. Kessl, F., Lorenz, W., Otto, H.-U. & White (Ed.), European Social Work - a compendium (pp. 229–272). Oldenburg: Barbara Budrich.

10.2. Section 2: ethical considerations in participative research

Aim: Participatory approaches to research demand a heightened level of attention given to ethical issues. This section prepares for the dilemmas that have to be faced in this line of research and for the required competences in addressing power issues.

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

| Ethics and law |

Legal obligations and constraints on research approaches |

In which areas does my research project touch on How am I prepared for dealing with possible discrepancies and conflicts between these frameworks? |

|

Ethics and |

Ethics and interests: Research is not limited to “recording” existing conditions of reality but has the purpose of questioning their Participative research is therefore likely to encounter conflicts regarding |

What interests does my proposed research project imply / express? On “whose side” do I stand with |

|

Benefits of upholding ethical |

Knowledge production value in different contexts and their interrelationship: |

What are the declared, what are the hidden outcome objectives of my research project? Which conflicts may arise from the incompatibility of objectives in the different context scenarios? What are my primary value objectives? |

Resources:

Banks, S., Armstrong, A., Carter, K., Graham, H., Hayward, P., Henry, A., Holland, T., Holmes, C., Lee,

A., McNulty, A., Moore, N., Nayling, N., Stokoe, A., & Strachan, A. (2013). Everyday ethics in community-based participatory research. Contemporary Social Science, 8(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2013.769618

Biesta, G. (2011). The ignorant citizen: Mouffe, Rancière, and the subject of democratic education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 30 (2), 141–153.

Forbat, L. and Hubbard, G. (2015) ‘Service user involvement in research may lead to contrary rather than collaborative accounts: findings from a qualitative palliative care study’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(4): 759–69.

Goldstein, L.S. (2000) ‘Ethical dilemmas in designing collaborative research: lessons learned the hard way’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 13(5): 517–30.

Iphofen, R. (2011). Ethical decision making in social research: A practical guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Minkler, M., Fadem, P., Perry, M., Blum, K., Moore, L., & Rogers, J. (2002). Ethical dilemmas in participatory action research: A case study from the disability community. Health Education and Behaviour, 29(1), 14–29.

Rowan, D., Richardson, S. & Long, D. D. (2018). Practice-informed research: Contemporary challenges and ethical decision-making. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics, 15(2), 15-22

10.3. Section 3: research contextual consideration

Aim: Participation is a very topical issue in research and funding programmes. Students should gain an overview of current trends in order to take ownership of their own understanding of the value of participation in research contexts.

| Theme | Topic | Guiding questions |

| Funding conditions |

Case study of selected international and national research programmes relevant to social work issues and their funding agendas |

How does the “participation terminology” of selected programmes compare to my understanding of |

| Contractual conditions |

Overview of types of contracts in research funding programmes – flexibility and limitations with regard to changes arising from the implementation of a participation approach |

To what degree can partners modify the objectives of the research project within the |

|

Dissemination and |

Ownership and authorship types of research findings

|

What types of rights and What happens after the ending of a project period? |

Resources:

Banks, S., Armstrong, A., Booth, M., Brown, G., Carter, K., Clarkson, M. and Russel, A. (2014). Using co-inquiry: community-university perspectives on research, Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 7(1): 37–47.

Chevalier, J.M. & Buckles, D. J. (2019) Participatory Action Research. Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry. London: Routledge

Driessens, K., and Lyssens-Danneboom, V. (eds.). (2022). Involving Service Users in Social Work Education, Research and Policy: A Comparative European Analysis. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Herr, K. and Anderson, G. (2005) The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty, London: Sage.

10.4. Section 4: The RPP Model applied to participative research

Aim: in this section PhD candidates will critically examine the opportunities and obstacles encountered in putting together and implementing a participative research project. In correspondence with the cyclical nature of the model this process will have to be repeated at regular intervals in relation to the planning and implementation process.

This part of the module requires the direct involvement of the academic supervisors of each thesis in the planning and timing of each presentation.

Service user group representatives who are partners of the respective research topic and project play a partner role in accordance with the principles and guidelines for participative professional learning outlined in the Guide Book.

Since the topics constitute “packages” in a circular arrangement, the sequence in which they are being addressed allows for flexibility and for repetitions.

For background and implications for participative learning and practice approaches see the section in the Practice Guide.

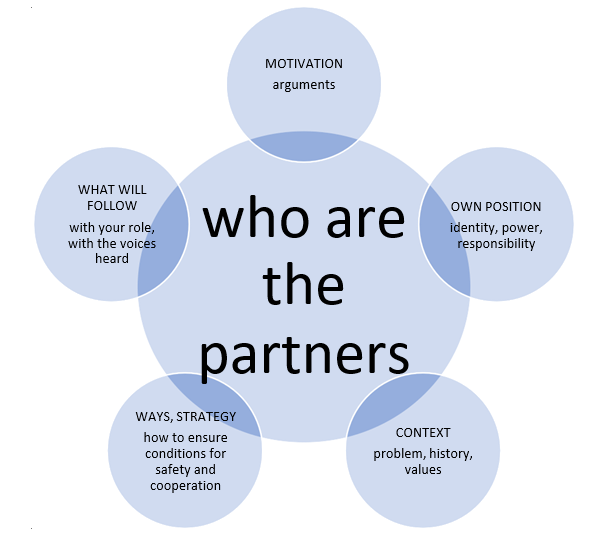

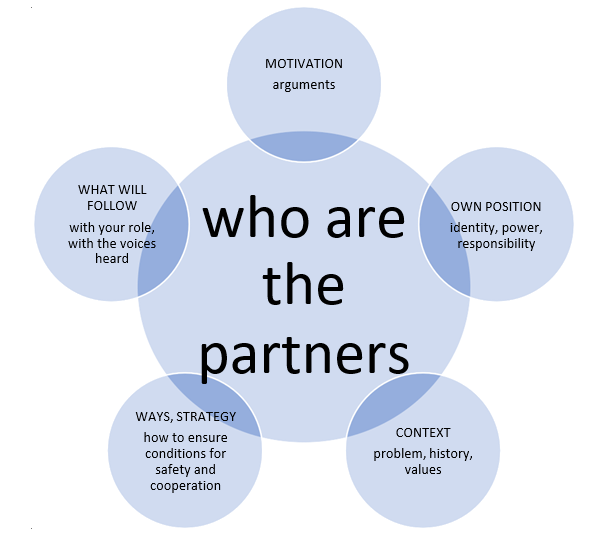

| Package | Topics | Guiding questions |

| Motivation |

Intellectual pathways leading up to the topic choice Biographical motivation and corresponding experiences Political and ethical principles that will be “tested” by the proposed research topic |

Which parts and themes of my previous studies connect me to this research topic? Can I translate my personal motives into motives that To what extent am I prepared |

| Partners |

In most cases of practice-relevant research access to service user groups will be Finding partners at both levels requires considerations of |

Which service agencies can best mediate access to user groups? Can the involvement of agencies and professionals What is “typical”, what is probably person-specific about the life experience of a service user? |

| Context |

The actuality of the proposed research topic in academic discourses nationally and internationally The actuality (or lack of) of the proposed research topic in current political debates nationally and internationally Origins of the research interest (funding programme / agency, service agency, user group commission, own commission …) Research funding conditions as expressions of a political agenda |

In which academic contexts is the topic being discussed? To what extent are the academic discourses based on participative research? What are the links between academic and political interests in the topic? Can the funding conditions for research topic affect the political treatment of the topic? |

| Own position |

Participative approaches as part of the research funding conditions and their Issues of power differentials – risk of academics determining “the agenda” for practitioners and for service users and ways of addressing this risk Distinguishing own expectations from those of other partners – issue of “raising Own position in the scientific community |

How can I avoid that the participative approach may be perceived by service users as “tokenism”? To what extent can I relativise my power position as an academic and in what way can power differentials be Does my proposal raise expectations among service users which cannot be fulfilled? What are the implications of choosing a participative approach for my career |

| Research strategies |

Examination of participative research Status of research as “independent” or “contractual” Boundaries of confidentiality and privacy |

What are the strengths and Do my research strategies allow me to distance myself from the agendas of the partners? How do confidentiality conditions impact my research |

| Expected implications of results |

Modes of presenting results (causal explanations, descriptive phenomena, shared narratives …) “Ownership” of research findings – whose benefit? Dealing with unexpected results Modes of dissemination |

Who and what determines the mode of presenting my How can “benefits” arising from findings be shared? How do I prepare for findings that might render partners (more) vulnerable? |

Resources:

Cancian, F. (1993). Conflicts between activist research and academic success: Participatory research and alternative strategies. American Sociologist, 24(1), 92–106.

Cornwall, A. (2008) ‘Unpacking “participation”: models, meanings and practices’, Community Development Journal, 43(3): 269–83.

Dodson, L., Piatelli, D., & Schmalzbauer, L. (2007). Researching inequality through interpretive collaborations: Shifting power and the unspoken contract. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(6), 821–843.

MacFarlane, A., Galvin, R-, O'Sullivan, M., McInerney, C., Meagher, E., Burke, D. and LeMaster, J. W.. (2017). Participatory Methods for Research Prioritization in Primary Care: An Analysis of the World Café Approach in Ireland and the USA. Family Practice, 34 (3), 278-84.

Malka, M., & Moshe-Grodofsky, M. (2021). Social-work students’ perspectives on their learning process following the implementation of community based participatory research in a community practice course. Social Work Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1989398

Pain, R., Kindon, S., & Kesby, M. (2007). Participatory action research: Making a difference to theory, practice and action. In S. Kindon, R. Pain, & M. Kesby (Eds.), Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp. 26–32). Abingdon: Routledge.

Van Der Vaart, G., Van Hoven, B. and. Huigen, P. P. P. (2018). Creative and Arts-based Research

Methods in Academic Research. Lessons from a Participatory Research Project in the Netherlands. Forum, Qualitative Social Research, 19 (2)

Practice example: See Practice Guide “The participation of families in poverty situations in research on child and family social work: learning from a Belgian social work research project”

11. 3rd cycle Competence levels according to the Dublin Descriptors

| 3rd cycle | Competences | |

| Knowledge and understanding |

Systematic understanding, |

Can place participatory research approaches in the wider context of research methods and their political implications |

| Applying knowledge and understanding | Design and implement scholarly research | Can design a coherent participatory research project; has considered difficulties, conflicts and how to address them |

| Making judgements |

original research that extends the frontier of knowledge; |

Has a solid grounding in ethical considerations implied in participatory approaches to research; can weigh up benefits and risks for different partner groups and research levels |

| Communication skills |

can communicate with their peers, the larger scholarly community and with society in general about their areas of expertise |

Can communicate aims and objectives sensitively and authentically to all partner groups; can give a grounded public account of research objectives, methods and outcomes |

| Learning skills | Promote professional, social and cultural advancement |

Can contribute to the further development of participative research approaches in social work and their use in professional practice |