5. Conclusions

5.1. A Framework for Analyzing Factors for User Participation in Social Work

As discussed above there was considerable variation in the way that social work practice, policy, education and research helped the project team understand issues of service user empowerment. The drivers behind user involvement differed considerably between the countries examined, partly due to diverse historical, political, cultural or academic traditions. It is important to reflect on how such issues have impacted on the development of social work education and social work practice in the jurisdictions examined.

A next step within the INORP-project is to examine way in which service user involvement is reflected in social work education and understood by students, as reflected by Speicher (2014, 199) in the context of the UK: “During the past two decades, the attention towards service user involvement in social work education has been growing. Thanks to new guidelines (DH, 2001), it is mandatory to actively involve service users and carers in all stages of social work university education in the United Kingdom. This means that service users and carers need to have a say in the development of a new social work curriculum, the teaching activities themselves and also in practice training. The latest development in the area has been mainly thanks to the consistent engagement of service user groups. The initiative came largely from disabled people’s movements, who wanted to receive higher quality services.” Such ideas are also evidence in Ireland which, despite its different type of welfare regime, has a similar tradition of strong state regulation, social work pedagogy and practice to the UK. From a Finnish perspective, despite a considerable amount of research on user involvement in social work, user involvement is reflected rather weakly in curricula, or as a means for curriculum development at universities. In Finland, universities have considerable academic freedom to define their curricula, and politically defined requirements like the British one are not considered to fit into this general idea (in Sweden, for instance, the situation is different).

Another subject for further reflection upon is the question of ‘systemic legacies’, which are evident in the Portuguese and Czech country reports. In such countries where there may be limiting factors for (future) user involvement and democratic channels and pathways for citizens/users/user organizations in influencing welfare policies considerations about the role of social workers and other actors are relevant.

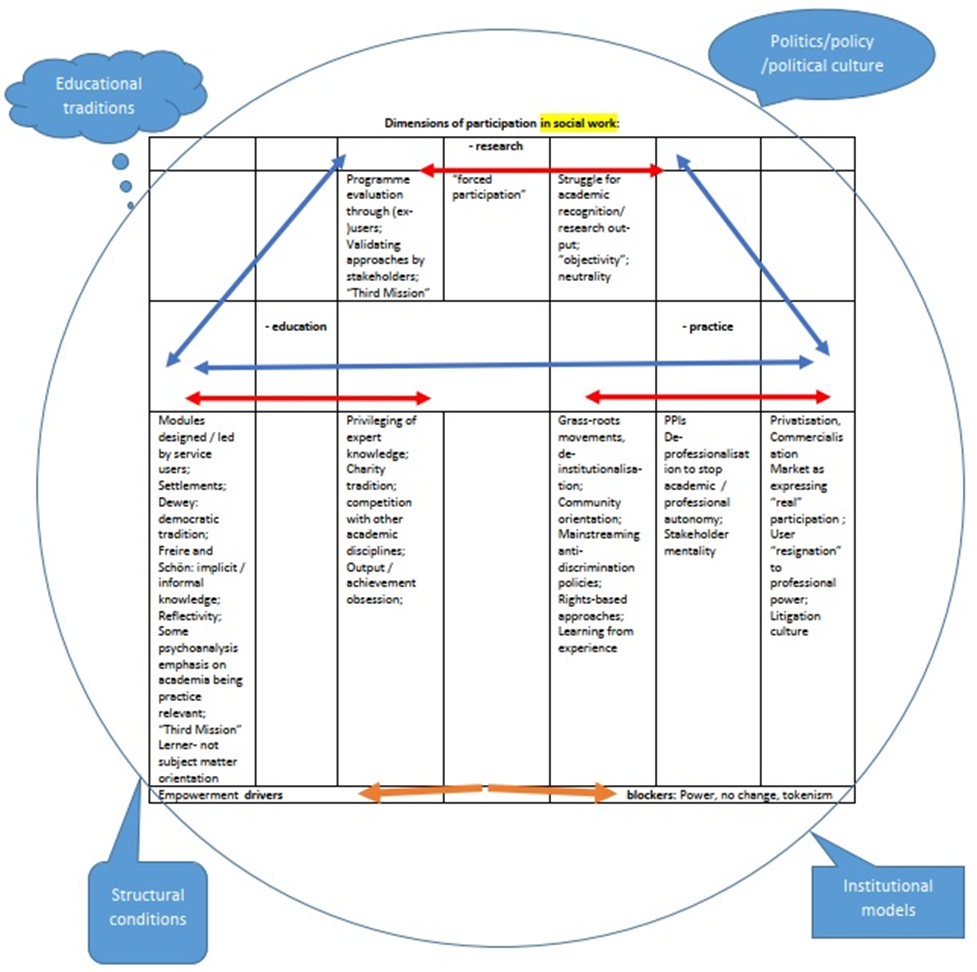

A general conclusion that may be drawn on the basis of the country reports is that it seems to make sense to analyse the nature of the state (scope, quantity and focus) of research on user participation as this relates to social work education and practice/service provision. Thus, both when analysing the outcome of country reports, and in future work/activities within the INORP-project, it is important to critically examine further the links between teaching, research and practice when user participation matters are concerned. It seems especially important to analyse this ‘triangle’ of teaching, research and practice (see Diagram 1) with a focus on power aspects: questions remain about what are the drivers and facilitators of teaching/research/practice (when it comes to user participation in social work) and what are the resistance factors/blockers of user participation, with the risk of leading to tokenism an falseness. It is also important to consider issues of power and the use and misuse of knowledge in this field, and how social policy frameworks inform all 3 areas (political principles become reproduced at the levels of research, education and practice) but they do not determine the form and level of participation in national contexts uniformly.

Diagram 1: The ‘triangle’ of teaching, research and practice with a focus on power aspects