Output 1

| Site: | MOOC Charles University |

| Course: | Reflexivity and participation in communities |

| Book: | Output 1 |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 14 February 2026, 9:48 AM |

Description

1. Output 1

Innovation by supporting reflexivity and participation

A FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING AND REFLECTING ON MODES OF USER PARTICIPATION IN SOCIAL WORK IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

CONCLUSIONS BASED ON ANALYSES OF SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL ARTICLES FROM THE COUNTRIES PARTICIPATING IN THE ERASMUS+ INORP-PROJECT

A framework for analyzing and reflecting on modes of user participation in social work in a comparative perspective - Conclusions based on analyses of scientific journal articles from the countries participating in the ERASMUS+ INORP-project

By Helena Blomberg1, Christian Kroll1, Jim Campbell5, Sarah Donnelly5, Zuzana Havrdová2, Dana Hradcová2, Idalina Machado4, Sara Melo4, Walter Lorenz2, 4, Pavla Povolná2, José Alberto Reis4, Griet Roets3, Rudi Roose3, Laura Van Beveren3

--------

1University of Helsinki (Leader, Output 1); 2Faculty of Humanities, Charles University (Project leader); 3Ghent University; 4Higher Institute of Social Work of Porto; 5University College Dublin

This report constitutes Intellectual Output 1 as laid out in the INORP Project Plan

2. Introduction

The primary aim of this report is to summarize and reflect on the overall results of the first steps in the three-year project “Innovation by supporting reflexivity and participation: Strengthening education and professionalization of social work on the border of other professions” funded by the Erasmus+ Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices program, 2020-2023. Five European universities are partners in the project: UNIVERZITA KARLOVA (Czech Republic, project leader), UNIVERSITEIT GENT (Belgium), HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO (Finland), UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN (Ireland) and Cooperativa de Ensino Superior de Serviço Social (Portugal).

This report concludes by presenting a framework for analyzing and reflecting upon modes of user participation in social work in a comparative perspective, which aims at providing a tool to be utilized by students and teachers when working on issues regarding user participation in social work.

The project has its background in the assumption that social workers have an important role as professional partners of disadvantaged, aging, and health-challenged people who are at risk of not having a strong enough voice and position as citizens in society’. The project has as an objective to ‘bridge skill gaps and develop capacity in participatory and inclusive approaches and collaborative reflexive skills among social and health work students and teachers by developing new learning and teaching tools. The project will use a partnership approach to explore and critically assess the way in which the different histories and social-political backgrounds of five different countries contribute to our understanding of these important areas of social work policy, practice and education (Lorenz, Havrdova & Matousek, eds. 2020).

The first step in our project was to conduct a national and European journals analysis. The aim was to provide insights in the similarities and differences among the participating countries and to establish the groundwork for developing the methodology in the following four project outputs. These future outputs would explore and design the types of skills and competencies that were important for reflexive decision making taking by social workers when engaging with service users and other stakeholders. In doing so the project team aims to appraise a variety of approaches that can be best used to delivery participatory interventions and partnerships, leading to a practice guide, among social work and health care students and the area of curriculum development. The ‘the overall objectives of the journal analysis was to identify and learn about the changing nature of the participative social work research in the participating countries with regard to their different history, culture and social and health care systems and to examine the benefits and challenges affiliated with the different ways of conducting the participatory research, such as engaging with the research participants/clients and employing collaborative reflexivity in solving complex social problems in the community.’

The comparative journal analysis was viewed to be constructive and innovative, particularly because the project countries, and their welfare regimes, represent diverse cultural and historical traditions in Europe, including East-West and North-South dimensions (Eikemo et al., 2007) with different participative approaches in the policy and social and health care systems in the respective countries. Such an analysis could contribute to a deeper understanding of the nature of participatory approaches in social and health care.

3. A review of literature

The discussion among the project participants at transnational meetings revealed variations in the way that the literature should be reviewed, for example in terms focus, ranking order, search concepts, methodology and possible comprehensiveness of country reports. There were concerns about the expected magnitude of the relevant national literature. For these reasons guidelines were developed to provide a flexible, ‘middle way’ in searching the literature that could be applied to all partner countries and which would make it possible to analyze the national reports also from a comparative perspective.

A number of core factors were important to explore:

- The ways in which participation of service users is a key challenge/complexity for social work professionals which required practitioners and educators to be reflexive, in order to establish answer the question: what do service users consider supportive?

- These challenges are relatively new to policy and practice in fields of social and health care, it was important to contribute to an analysis of how such ideas and practices are used by partner countries

- User participation may have varying meanings and take different forms, resulting in a variety of complex challenges, which may, or may not, be taken into consideration by researchers or practitioners.

Against this background, the aims of the literature analysis were to provide a knowledge basis for university teachers, students and practitioners when learning about historical and contemporary differences (and deficits) in user participation approaches in social work research and practice in the partner countries. It was agreed that the interfaces between the social work and health care professionals would be of common interest to the project team, given the nature of their welfare regimes. According to the project plan an aim was to explore the literature in terms of a (self) critical, reflective approach to user participation in the development of services, also the degree and types of direct or indirect references to reflexivity in the reviewed literature, both by researchers themselves and within the types of user participation studied. Furthermore, the findings of the literature review was also meant to function as a source for students taking part in our later project activities, especially when identifying and/or reflecting on good practices on service user participation, for instance, by conducting case studies of their own.

During project meetings, various types of approaches to reviewing the literature (Davies et al. 2019), for example systematic, scoping, integrative, and rapid reviews) were discussed. It was agreed that the most realistic way ahead seemed to be to conduct a ‘light variant’ of the type of scoping review described by Arkseys & O'Malley (2005). They described five stages in conducting a scoping review: Stage 1: identifying the research question; Stage 2: identifying relevant studies; Stage 3: study selection; Stage 4: charting the data Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results. These steps enabled the construction of a national report each participating university, as guided by the document in Appendix 1.

4. Literature review results

4.1. A varying prevalence of research on user participation

The literature review proved to be more challenging to perform following the guidelines in Appendix 1, than originally thought. In two of the countries there appeared to be very little published in the field of user participation in social work, and even less on issues combining user participation and reflexivity. In the Portugal case study there were no hits, even when a very open research strategy using Google and Google Scholar search engines was used. An in situ library search for any documents that would match with the criteria did not prove more successful. After a collegial consultation, the Portuguese members of the team found one book chapter related to the subject, recently published in Brazil.

The review in the Czech Republic (CR) yielded a moderate result in terms of the amount of research publications (five), this was achieved by widen the search to publications of more than five years old. These publications were based on studies conducted by teachers from only two of CR’s 13 universities that are regular and/or irregular members of the Association of social work educators. These limited numbers of research references are in contrast to the clear interest in issues of user participation, as expressed in many professional publications, and of using it within various fields of practical social work in the country.

In the case of Ireland, the authors drew upon their knowledge of relevant Irish literature, most of which does not refer directly to social work and participatory research approaches. They added to this knowledge by searching the Google Scholar and the Scopus databases, using the search terms: social work + participatory research + Ireland to confirm that all relevant, social work related literature was captured. The Irish report focuses on examples of different approaches to participatory research and it gives a number of more localized examples of practices across a number of client groups, for example young people in state care and older people in hospitals and other institutions. It was apparent that there was moderate number of studies on these topics, but relatively few from a social work perspective.

These finding are in contrast, in particular to two of the other countries, Belgium and Finland. Here, the literature searches resulted in a plethora of publications and attempts at systematizing the publications proved challenging, with the national teams choosing different paths in the search process. The Belgian literature search resulted in a number of publications dealing with participation and reflexivity in social work, which were systemize through a more chronological approach. The country report points at a major emphasis on issues of reflexivity in social work (including practitioners, researchers, and educators) and, in particular, on participatory and democratic approaches in social work research, policy and practice development at the academic level in Flanders. This focus is explained by the ‘Anglo-Saxon turn’ within social work academia in Flanders during the last 20 years: As a consequence of a growing pressure to publish in peer-reviewed journals, the reading and writing habits of Flemish researchers have changed. The French speaking social work researchers in Belgium, in turn, are mostly in contact with developments in France, Quebec and French-speaking Switzerland. The scoping literature by the Belgian team focuses on English language journal articles published by researchers dealing with these developments in academia in Flanders, as well as on contributions in Dutch.

As with Belgium, the Finland team reviewed a fairly large amount of publications. These were thematised into three categories in order to achieve an overview of their content: The categories included a) studies about action/ activities/ processes/ forms/ methods of participation, b) studies about experiences/ feelings/perceptions/ attitudes/ interactions related to participation, and c) studies about legislative/ political/collective discourses on participation. The review indicated that the experiences of service users is a well-researched area. Many studies highlighted how service users perceived their position to be one characterized by conflicting positions and expectations. At one level they were supposed to be active agents in charge of their own lives, but, at the same time, they are had to adapt themselves to the demands and logics the service system (Närhi et al. 2015), resulting in a kind of ‘hybrid user services’ (Valkama 2012). Professionals interviewed in the studies appeared to have limited concerns about the practical implementation of user participation, or means to increase it (for example through the notion of ‘participation as action’). One reason for this seems to be that the service system ‘pre-defines’ participation; (certain forms of) participation in the public service system are considered far more important or legitimate than participation in a community or society at large. Even though social workers tend to be critical about the tendency to pre-define what user participation should be there are some perceived problems with the profession’s views on this issue. Närhi et al. (2015), for example, note that social workers rarely, even rhetorically, suggest any concrete action about how user participation could be strengthened (for example through collective action or collective participation). This maybe be, the authors suggest, reflect a weak Nordic tradition of understanding of user movements within (social)services.

4.2. Exploring the country contexts of participation

The country reports used the findings from existing literature on user participation in social work as well as descriptions of the social work context in each country, to generated questions about similarities and differences between the countries. Project members were particularly interesting in exploring issues of power relations between various actors and institutions involved in the process of facilitating and/or promoting user participation, and how these affected issues of policy, practice and education in the countries. These discussions considered pivotal issues to be addressed when summarizing the results of the contribution of the project’s first part.

In conclusion, based on the separate country reports and discussions among project members at the monthly transnational meetings of project the central questions to be considered were as follows:

- What is the role of social workers in user involvement/participation in the partner countries and what is the relation between social work practice and research in these countries?

- Who is involved in facilitating/promoting user participation?

Below, these questions will be briefly discussed.

(1) As already mentioned, the individual country reports indicate that there is considerable variation in the level of published research on this topic in the respective partner countries to help us understand issues of user participation in the partner countries. With this in mind, partner countries agreed to widen the knowledge search to include more narrative and personal views of project participants on how service user participation in social work occurs. The point here is that, although there may not be studies carried out in some countries, there is practice evidence and wisdom which highlights a variety of traditions of, user participation in policy and practice development. The rather weak position, or short history, of social work within academia is emphasized in some of the country reports (Portugal, Czech Republic), perhaps because of the history of the profession, education and research traditions. For example, the Portuguese country report points out that, the reconceptualization of social work education in Portugal after the collapse of the dictatorial State in 1974, followed by a period of great dynamism, marked by many social movements, and social and political conflicts gained great visibility. The Revolution set the ideal conditions for social workers to perform alternative forms of intervention, moving away from the assistance-focused practices characteristic of the former authoritarian rule. Incited by the new progressive political agenda, social workers stood at the forefront of the Revolution, working alongside grass-roots mobilizations and experimental participative projects, overtly assuming political stands. (Silva, 2018).

In Belgium, where social work has not received full recognition on a university academic level in the French speaking part of the country, there are variations in policy and practice paradigms. In the Dutch speaking area research activity has been more developed, and at the practice level, user participation seems to be an important issue. This can be partly explained by the ways in which this issue has been actively promoted and supported in social policy and by social movements, creating a tradition of ’experts by experience’ in social work research, policy and practice developments that bring forth a critical-normative and reflexive professionalization of social work.

In the Czech Republic, social work has long traditions; however, it was interrupted not only by the two wars, but also by 40 years of a communistic system, which suppressed human rights and civil society. The full recognition of university academic level social work was received after 1990, and has later gained further strength through doctoral programs at four Czech universities. Since 2006, law regulates the position of social workers. The idea of participation was supported particularly in the sector of NGO services. However, in the governmental sector, as in the sector of the traditional residential services, the organizational cultures were blind to real user participation. Reflexivity has been practiced particularly when it comes to developing external supervision in social work since 1995.

In Finland, all social work programmes, and in Ireland most social work professional are educated to the Master’s level and there is growing attention to the importance of evidence based and/or evidence informed practice, in Ireland also supported by doctoral studies programmes. In both countries, it is necessary to register to a national body for acquiring the right to use the title of social worker and to practice as a social worker. Yet, as in other countries, change in the area of user participation in services seems to be hampered either by a lack of perceived possibilities, or of concrete actions aiming at, altering existing modes of provision.

It was evident from the country reports that there was variety, complexity and fluidity of the concepts that were being used to understand service user participation. Examples of these include, for example, participation, user participation, involvement user/customer involvement, user engagement, empowerment, engagement, social inclusion, (partner) collaboration, partnership, customer driven orientation and agency. Thus, ‘user participation’ does not have one all-embracing definition or meaning within or between the participating countries. Noteworthy is also that the goals of user involvement are often not in focus in the literature. User involvement may not be an end in itself, but rather it can be viewed as a means to enhance service user’s agency or strengthen democratic citizenship.

(2) Who is involved in facilitating/promoting user participation?

The country reports highlight the way that types of user participation has grown during the last decades. It can be argued that it is increasingly viewed as a way of improving social and healthcare services, but with rather different stakeholders as main driving forces. Contemporary approaches emphasis the notion of the concept of a vehicle for (re)defining power relationships between researchers, practitioners and clients/consumers, utilized by politicians, the academia, the public and private sectors and civil society. However, real shifts in power relations seem often to have remained rather modest in the participating countries. In this sense, there are substantial similarities between the countries, despite prevailing variations in historical-institutional legacies, the (relative) position of social work and research opportunities. The concern is that service user participation remains, to an important degree, tokenistic in many examples.

In some cases, however, there appear to be partly diverging explanations for rather modest shifts in ‘real’ power relations. For example, in the case of Finland, user participation at the institutional level is rather weak, yet individual social workers and agencies sometimes have adopted a rather critical stance. In general, however, is a limited tradition of increasing user participation through enhancing their collective action or collective participation. Social work remains to a great extent a public, ‘authority-driven’ activity and user participation is not embedded in the daily work of street-level workers, at least not as more concrete action (although perhaps as a “mind-set”).

Another aspect to be considered is the role of ‘funders’ as a driving force affecting the position of user participation in research and practice. For example, in Portugal, where social work is not a registered academic discipline, there is little or no funding opportunities to fund participatory (or other) research. Belgium and Finland have a much longer established tradition of participation in social work research, but, at least in Finland, there have not been that many (‘outside’) funders for academic research in social work. Ireland’s shift to PPI also seems to have also been influenced and driven by the requirement of funding bodies. It generally the case that little social work and health care funding in Ireland will be agreed unless there is core involvement of service users in the design and delivery of research projects. Again, it would seem to be relevant to reflect on further as regards these issues. It remains a question as to why research funding bodies in some countries require the involvement of users in the research process and others not. Where there are funding opportunities which encourage participatory approaches may lead to more meaningful studies on service user participation in social work research.

Another important issue arising from the country reports concerns the several similar challenges in many of the participating countries, when it comes to factors enabling or hindering (increasing) user participation in social work. As is mentioned in the Irish country report, the international literature on forms of participation suggests a number of challenges and opportunities. Of particular concern is the tendency towards ‘tokenism’ despite the intention of policy makers and some professionals. Notions of resistance to change might be explained by exclusionary professional attitudes; professions spend years learning about knowledge and skills which some believe cannot be subject to sharing through a transfer of power to service users. Some of the country reports also raised the question of forced participation, in which the outcomes of different participatory approaches and interventions may reinforce the problems that they intended to solve.

Some service users may be comfortable with this inequality, they want the expert to diagnose or direct. Even where individuals wish to engage with service users and become more inclusionary, organizational cultures are difficult to shift. Sometimes service user empowerment is used by governments and politicians to break down professional solidarity and replace state provision with market-based interventions.

Thus, although user involvement (or participation) in social work research (and as well as in education and practice) is considered desirable among almost all partners participating in the INORP-project, the question remains how realistic it is to expect real and authentic redistribution of power. This appears to be contingent on the involvement of different stakeholders representing governments, large NGOs or academia which determines which resources to initiate and what issues to define and who should and could be involved. Participation is also often embedded in projects and activities which do not live up to the genuine aims of participation, or the projects are too short-termed.

5.1. A Framework for Analyzing Factors for User Participation in Social Work

As discussed above there was considerable variation in the way that social work practice, policy, education and research helped the project team understand issues of service user empowerment. The drivers behind user involvement differed considerably between the countries examined, partly due to diverse historical, political, cultural or academic traditions. It is important to reflect on how such issues have impacted on the development of social work education and social work practice in the jurisdictions examined.

A next step within the INORP-project is to examine way in which service user involvement is reflected in social work education and understood by students, as reflected by Speicher (2014, 199) in the context of the UK: “During the past two decades, the attention towards service user involvement in social work education has been growing. Thanks to new guidelines (DH, 2001), it is mandatory to actively involve service users and carers in all stages of social work university education in the United Kingdom. This means that service users and carers need to have a say in the development of a new social work curriculum, the teaching activities themselves and also in practice training. The latest development in the area has been mainly thanks to the consistent engagement of service user groups. The initiative came largely from disabled people’s movements, who wanted to receive higher quality services.” Such ideas are also evidence in Ireland which, despite its different type of welfare regime, has a similar tradition of strong state regulation, social work pedagogy and practice to the UK. From a Finnish perspective, despite a considerable amount of research on user involvement in social work, user involvement is reflected rather weakly in curricula, or as a means for curriculum development at universities. In Finland, universities have considerable academic freedom to define their curricula, and politically defined requirements like the British one are not considered to fit into this general idea (in Sweden, for instance, the situation is different).

Another subject for further reflection upon is the question of ‘systemic legacies’, which are evident in the Portuguese and Czech country reports. In such countries where there may be limiting factors for (future) user involvement and democratic channels and pathways for citizens/users/user organizations in influencing welfare policies considerations about the role of social workers and other actors are relevant.

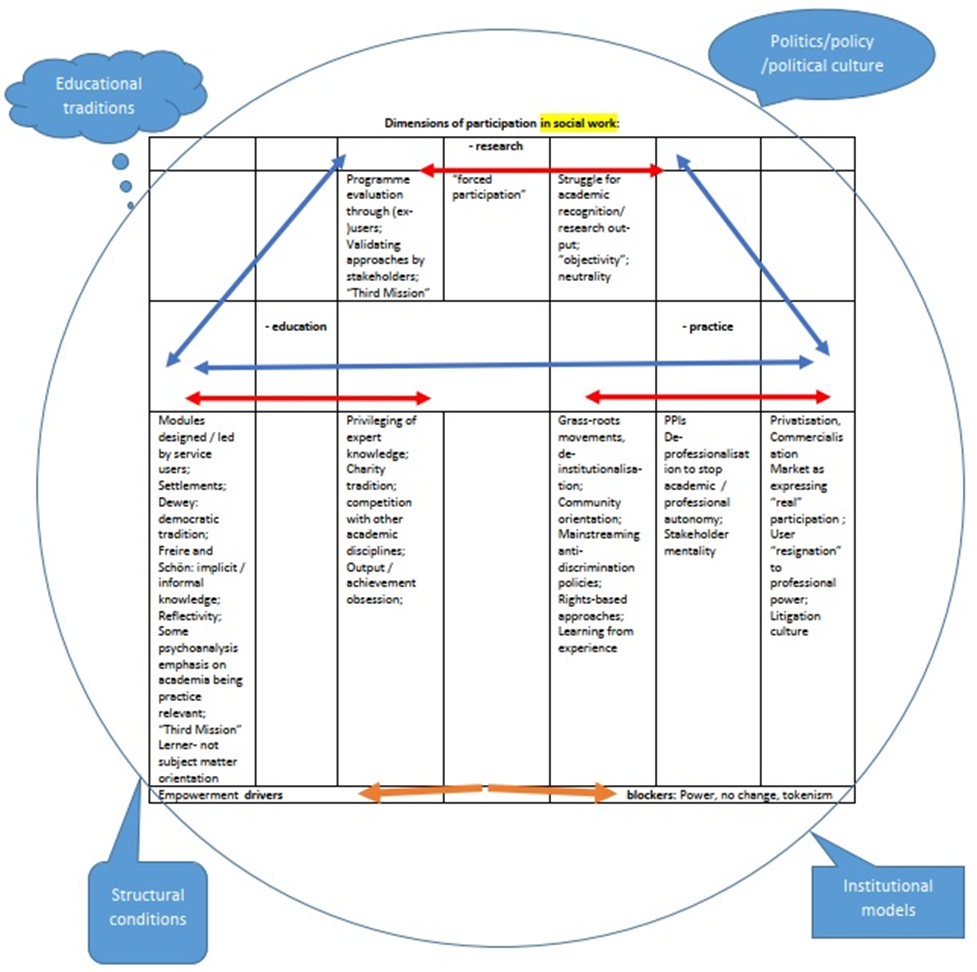

A general conclusion that may be drawn on the basis of the country reports is that it seems to make sense to analyse the nature of the state (scope, quantity and focus) of research on user participation as this relates to social work education and practice/service provision. Thus, both when analysing the outcome of country reports, and in future work/activities within the INORP-project, it is important to critically examine further the links between teaching, research and practice when user participation matters are concerned. It seems especially important to analyse this ‘triangle’ of teaching, research and practice (see Diagram 1) with a focus on power aspects: questions remain about what are the drivers and facilitators of teaching/research/practice (when it comes to user participation in social work) and what are the resistance factors/blockers of user participation, with the risk of leading to tokenism an falseness. It is also important to consider issues of power and the use and misuse of knowledge in this field, and how social policy frameworks inform all 3 areas (political principles become reproduced at the levels of research, education and practice) but they do not determine the form and level of participation in national contexts uniformly.

Diagram 1: The ‘triangle’ of teaching, research and practice with a focus on power aspects

5.2. Examples of factors at different levels affecting the ‘triangle’’

Examples of factors at different levels, affecting the ‘triangle’ are, for instance:

Level of politics:

- Political culture (democracy, participation, history of social movements)

- Various notion of citizenship (conditional / unconditional): do citizens have a right to be heard /to co-determine – or do they have to “earn” such rights (by learning how to conform, to become educated, to have already achieved certain levels of citizenship competence)

- Perception of the role of the state’s guiding ideological principles (centralism, familialism, nationalism, populism as “participative””, direct democracy etc.

- Public administrative structures that either facilitate participation or represent barriers (for instance Federalism combined with subsidiarity – as against centralism where the “centres of power” are always perceived as being “far away”)

Institutional models:

- Preference for flat or strongly hierarchical organisations

- Organisational culture influenced by entrepreneurial-managerial principles (orientation towards “letting the best talents emerge” for increasing creativity, effectiveness or profit) or by “traditional bureaucracy” (where everybody is an autonomous expert in their own sector, leadership only coordinates)

- Recruitment policies (each function specified ab initio – or each function still to be developed by the personal input of the person recruited)

Educational traditions:

- “streaming”, selectivity of “talents” who can thereby ‘participate’ more actively than in non-selective, comprehensive, inclusive educational settings where the principle of participation by all kinds of talents “levels” the achievements

- Early childhood education models – more participation when educational facilities “take over” from parents or when parent can participate as long as possible in their own education of children

Structural conditions:

- Rural / urban conditions that structure social contacts

- Centre / periphery; contact and communication infrastructure (whereby physical proximity not necessarily participation enhances)

- Availability of public meeting places; democratically constructed neighbourhoods

It is therefore crucial to investigate what forces cause the respective polarisations in the various national and organisational national contexts and not to develop a universal “thermometer” with which to measure the “participation health” of a country, study programme, research project or practice organisation.

The factors create multi-dimensional mixes of participation elements and forms that are not linear like the “ladder of citizen participation (Arnstein 1969): for instance a highly centralised state (e.g. the UK) can also give rise to very vociferous civil society (oppositional) “bottom up” movements, whereas participation in Germany (subsidiarity tradition) is much more institutionalised, channelled through “mediating organisations” so that participation takes a more formal, less “critical” form, while in Italy for instance a highly centralised political culture at the same time makes people shift their participation to family, clan, regional or interest-bound structures out of resignation that “real” participation in the complex, bureaucratic and often oppressive forms of state power is impossible right from the beginning. In each case it is difficult to rank the degree of possible participation because for instance in Italy people would not desire to have a greater share in central state affairs and prefer to devote their energies to participation in local and private contexts

In Finland, the nature of the mix of participation elements seems to be almost opposite to that in Italy; the institutional model for service production rests on a cultural notion of “the state equalling society” (cf. Kettunen 2001), in which there are no general expectations/fears of the state (and in social services, the municipalities) and of its/their institutions not serving the interests of society. But it also means third sector organizations, including, e.g., user’s organizations, are often getting financial support from the state, and they are utilized in relation to service production/as (financially subsidized) service producers (example: in the training of “experts of experience”), while even the interest in expanding “user involvement” seems to have been promoted largely by the public administration (as a means for developing, not substituting or de-professionalizing, public social services. At the same time, this hardly means any attempts at “radical” forms of “user participation”, and has not, at least thus far, resulted in any common elements of co-production etc. in education while research into these issues seems fairly theoretical in nature.

The co-production of social /educational programmes or projects can produce a type and an intensity of participation in one type of political culture (e.g. UK as ‘opposition’ to the state – for example the “People First” movement) which cannot be directly compared with that of “participation in compensation for the state’s failings or indifference” in the Czech Republic – or the Finnish form of “participation to improve existing professional services”.

6. References

Arksey, H. and O'Malley, L. (2005), Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8 (1), 19–32, DOI: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arnstein, S. (1969), A Ladder of Citizen Participation, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224.

Davies, C., Fattori, F., O’Donnell, D., Donnely, S., Ní Shé, E., O.Shea, L., Prihodova, L., Gleeson, C., Flynn, A., Rock, B., Grogan, J., O’Brian, M., O’Hanlon, S., Cooney, M. T., Tighe, M. and Kroll, T. (2019, What are the mechanisms that support healthcare professionals to adopt assisted decision-making practice? A rapid realist review, BMC Health Serv Res 19: 960, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4802-x

Eikemo, T., Huisman, M., Bambra, C. and Kunst, A. (2008), Health inequalities according to educational level in different welfare regimes: a comparison of 23 European countries, Sociology Health Illn,, 30 (4), 565–582, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01073.x

Kettunen, P. (2001), The Nordic Welfare State in Finland, Scandinavian Journal of History, 26 (3), 225–247, https://doi.org/10.1080/034687501750303864

Lorenz, W., Havrdová, Z. and Matoušek. O. (eds.) (2020), European Social Work After 1989: East-West Exchanges Between Universal Principles and Cultural Sensitivity, Cham Springer.

Matthies, A-L, Närhi, K., and Kokkonen, T. (2018) The Promise and Deception of Participation in Welfare Services for Unemployed Young People, Critical social Work, 19 (2), 1–20, DOI: 10.22329/csw.v19i2.5677

Silva, P. G. (2018), Social workers in the Revolution: Social work’s political agency and intervention in the Portuguese democratic transition (1974–1976), International Social Work, 61(3), 425–436, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872816651706

Speicher, L. (2014), Service User Involvement in Social Work Education, in Elsen, S. and Lorenz, W. (eds.) Social Innovation, Participation and the Development of Society, Bolzen-Bolzano University Press, 199–210.

Valkama, K. (2012), Asiakkuuden dilemma. Näkökulmia sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollon asiakkuuteen. Akateeminen väitöskirja. Acta Wasaensia No 267. Vaasa: Vaasan yliopisto, Sosiaali- ja terveyshallintotiede.

7. Appendix 1

GUIDELINES FOR NATIONAL REPORTS FOR OUTPUT 1.

General notes

As our discussions have shown, there has been some variation among the partners regarding various aspects (e.g. the exact focus/ “ranking order” in terms of concepts, the scope in terms of the material to be included, the methodology, and comprehensiveness of the national reports) of this exercise. This seems to us as also partly related to the expected magnitude of the relevant national literature. Thus, our guidelines are an attempt at providing a “middle way” in the above respects, which we hope can be applied in all partner countries and which will make it possible to analyze the national reports also from a comparative perspective. Hopefully, the analysis resulting in O1 may also later serve as a basis for a joint scientific journal article. Therefore, we think the points of departure in the (national) analysis should be similar to those of a joint article.

As suggested by Griet, the points of departure guiding the analysis are:

- Participation of service users is a key challenge/complexity for social work professionals in order tobe reflexive, since they have to learn to take into account the question what service users consider supportive

- This challenge is particularly ‘new’ in relation to professional interfaces in the field of social andhealth care, and our analysis contribute to exploring work in diverse European countries on this topic

- User participation may have varying meanings and take different forms, resulting in a variety ofcomplex challenges, which may, or may not, be taken into consideration by researchers or practitioners.

Against this background, the aims of the (national) literature analysis that all project members conduct and report are:

- To provide a knowledge basis for university teachers, students and practitioners when learning abouthistorical and contemporary differences (and deficits) in user participation approaches in social work research and practice in the partner countries – with a particular focus on situations involving interfaces between the social work and health care professionals.

Since our project aims at providing a (self) critical, reflective approach to user participation in the development of services, also the degree and types of direct or indirect references to reflexivity in the reviewed literature, both by researchers themselves and within the types of user participation studied should also be a part of the analysis.

- Within our project, O1 should also function as a source for students taking part in our later projectactivities, especially when identifying and/or reflecting on good practices regarding user participation.

Based on these general considerations, we hope that you could conduct a review of the relevant literature on the subject in your country, following the more specific guidelines below:

On the methodology

During our meetings, we discussed various types of reviews (systematic reviews, scoping reviews, integrative reviews, rapid reviews etc. c. (e.g. Davies et al. 2019). After considering these, we have drawn the conclusion that that the most realistic way ahead seems to be to conduct a “light variant” of the type of scoping review described in Hilary Arksey’s & Lisa O'Malley’s (2005) article “Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework”

It includes five stages for conducting a scoping review: Stage 1: identifying the research question; Stage 2: identifying relevant studies; Stage 3: study selection; Stage 4: charting the data Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results. The guidelines below follow this general outline.

In our reviews, these steps aim to serve a flexible basis for the national report each participating university delivers. Thus, the steps can be applied to the prerequisites in the respective country.

However, is important describe your methodological decisions, so that the reader can understand your choices and procedures, and, for reasons of comparison, we hope you follow the stages listed below.

STAGE 1. THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS

As agreed on during our meetings, the research questions we should aim at answering on the basis of the analysis of research in/on you country is

What is the current situation and what can be considered main challenges regarding service user participation in social work in [country]?

When answering the question, special attention should be paid to aspects of professional interfaces as well as direct and indirect references to issues of professional reflection - to the extent that they emerge in the material.

In order to make the reader understand the context in which the question is to answered, the report should start by a brief contexualizing description of social work and its history and traditions in your country, with a special reference to issues of user participation.

Here, we suggest that authors depart from their personal (expert) understanding of the current national situation, of the historical factors leading up to the current situation, as well as of the current developmental traits as regards user involvement in their own country, and also the author’s expectations on what kind of research is expected to be found during the scoping review. Other personal perceptions on the current situation, e.g., whether there may be a “gap” between the professional discussion on user involvement and research on the topic, may be noted by way of introduction. Thus, everyone would use an approach/view similar to the one they had when joining the project in the first place – which could perhaps give the reports –and the subsequent parts of the project– an ‘extra dimension’.

STAGE 2: HOW TO IDENTIFY RELEVANT STUDIES

The aim of a scoping review is to establish the scope of a phenomenon/field as comprehensively as possible in order to answer the central research question(s). Thus, the search for studies/publications/sources via different sources is recommended: *electronic databases *reference lists *hand-searching of key journals *existing networks, relevant organizations and conferences”.

However, in our study, both for reasons of time & recourses and because the research published on the subject might be quite limited and not necessarily available through electronic databases, your sources should be chosen based on feasibility. Obviously, the most important criteria is that you include the sources consider relevant to the degree possible. Please comment on your choices of sources in your report.

Each participating country should focus on national research in a fairly broad sense: it should be in or on the national context. Thus, the research should either be

- published in your country or

- published abroad/or in an international journal/proceeding etc. and concern your country OR beauthored by a scholar from your country

In this way it is hoped that we can get a fairly comprehensive picture of the type of research on the topic going on in each project member country.

Both empirical, theoretical and other more debating-type scientific articles can be included.

The time span should be 5 years backwards (2015->), but also older studies, especially relevant for the field may be included if considered important.

The journals / publications included in your review should be the national one(s) mentioned in the research plan and other national publications (and European journals) you consider relevant.

a) Electronic databases etc.:

If you can use electronic databases, use the term *participation (and synonyms) *service user * social work (in national languages and in English) and other terms that you know are used to describe these same phenomena in your country.

Please remember to document which databases have been searched/used (+which years are covered, the date of the search), as well as which terms (in what languages) that you have used.

b) Reference lists

You may want to check the bibliographies of publications found through the electronic database searches (to what extent have they been included in the scoping exercise above).

c) Hand-searching of key journal(s)

We believe it might also be relevant to hand-search key journals/ other publications (even if you could use database and reference list searches) in order to detect relevant material.

d) Existing networks, relevant organizations and conferences

To the extent that you know/believe it to be relevant in order to get a fair picture of the research on our topics, web pages of and/or contacts to relevant national organizations etc. working in the field, could also be included in order to identify, e.g., unpublished scientific work that still seems for some reason to be important.

Please comment on your procedures.

STAGE 3. Selecting studies

At this stage, key studies addressing our research question should be selected, if the material is too vast to analyze in its entirety. Please comment on your choices.

STAGE 4: Charting/appraising the data

In our study, the dominating view among the project team members seems to be that there is no need to report details on all material found, but that references in the text to those publications found to be most relevant for answering the research questions is enough. (However, if not too strenuous, a list of the material found as an appendix would probably be valuable to some readers).

However, the main focus here is on charting and appraising the relevant research found: in what ways, by what actors, and in what publication fora are the topics of service user involvement in social work dealt with, is there a focus on professional interfaces, are there references to reflexivity? What are the most interesting research themes found, what are the main research insights, in your opinion?

STAGE 5. Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

Finally, a “narrative summary” (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005) on user participation in social work, based on the literature you have reviewed should be attempted. The focus should be on conclusions related to the research questions, and should also include comments on the extent and nature of references to professional interfaces and/or references to social worker reflexivity regarding service user involvement (either in study designs, or otherwise) in the reviewed material. Also, it would be nice if the author(s) would reflect on the published material in relation to their initial views and expectations (cf, STAGE 1), and on their (expert) knowledge of ‘what is going on at the moment’ in the respective country.

Reference;

Hilary Arksey & Lisa O'Malley (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8:1, 19-32, DOI: