PARTICIPATIVE RESEARCH EXAMPLE FROM BELGIUM

| Site: | MOOC Charles University |

| Course: | Reflexivity and participation in communities PT |

| Book: | PARTICIPATIVE RESEARCH EXAMPLE FROM BELGIUM |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 19 February 2026, 8:18 PM |

Description

The participation of families in poverty situations in research on child and family social work: learning from a Belgian social work research project

1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, the importance of the participation of people in poverty in social work research has been emphasised (Beresford, 2002; Beresford & Croft, 2004; Krumer-Nevo, 2005, 2016; Lister, 2002, 2004; Mehta, 2008). The essence of poverty has been framed as a structural problem of non-participation: people in poverty are excluded from the process in which poverty and anti-poverty strategies are defined (De Bie, Roets & Roose, 2013). 'Giving voice' has quite recently entered the realm of poverty research, based on the idea that:

"opening our ears to the voices of poor (...) is vital to the humanising of citizens and institutions, including research (...) and offers a unique potential contribution to the overall corpus of knowledge because it reflects the point of view of people on the fringes of society concerning their own lives, as well as society and its primary institutions" (Krumer-Nevo, 2005: 99–100).

Moreover, Freire (1972) argues aptly that non-poor people, such as social work researchers, who actually have the power to bring about social justice and social change often, and quite unintentionally, also maintain the status quo. Premised on the idea that people in poverty are experts by experience in poverty (Lister, 2004), engaging with people in poverty in participatory ways in social work research embodies a fruitful strategy for gaining an in-depth understanding of the complex and multifaceted nature of poverty as a social problem, and of the relevance of social work interventions.

In that vein, our example is based on a research project conducted in Flanders (the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium) in which the life histories of families in poverty situations were retrospectively explored. The aim of the research project was to identify which social work interventions in child and family social work were experienced as meaningful by the families for their mobility out of poverty (see Schiettecat et al., 2016).

In our example, we have used the guiding questions of the RPP involving six packages of focus to describe our experience.

2. Context

The research project was commissioned and financially supported by the Flemish Research Center on Poverty (VLAS: Flemisch Poverty Research Center), which aimed at developing strategies in policy and practice for child poverty reduction. VLAS rooted the mandate for research in the rationales of social policymakers across Europe, who have recently adopted an explicit focus on combating child poverty (European Commission, 2008). Whereas child poverty has, for centuries, been a stubborn problem in most European societies (Cantillon, 2011; Platt, 2005; Rahn & Chassé, 2009), it has only recently become one of the highest priorities of anti-poverty strategies. The aim is to generate tangible results from the efforts to combat child poverty across Europe, including poverty within families and its intergenerational transmission (Council of the European Union, 2006).

In framing child poverty as a problem that needs urgent action, it has been made the focus for interventions by practitioners in child and family social work (Platt, 2005). The children, along with the parents, who are perceived as responsible for the children's well-being, have become the central objects of intervention (Gillies, 2005, 2008; Schiettecat, Vandenbroeck & Roets, 2014). Anti-poverty strategies have, for instance, been increasingly directed towards prevention in early childhood education and care as a field of health and social care practice (Doyle, Harmon, Heckman, & Tremblay, 2009).

Therefore, this policy context allowed us to transfer our interest in realising a participative research design to this international social policy issue.

Reference: Schiettecat, T., Roets, G., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2015). Do families in poverty need child and family social work? European Journal of Social Work, 18(5), 647-660.

3. Motivation

The context for our ambition as researchers to work in participative ways with families, especially parents in poverty situations, stemmed from the acknowledgement that the individual responsibility of parents has increasingly been emphasised within a so-called 'parenting turn'. We see this as indicative of a climate characterised by explicit and implicit attempts to control and regulate the conduct of parents, particularly poor parents (Gillies, 2005; Lister, 2006). In the vein of a social investment paradigm, the child is positioned as the central object of intervention, which "divorces children's welfare from that of their parents" (Lister, 2006, p. 315-316). Poor parents are frequently portrayed "as making bad spending decisions and transmitting their attitudes and behaviours to their children" (Main & Bradshaw, 2015, p. 38). Parents have historically been treated as 'incapable' and 'underserving' because they are deemed responsible for dealing with the structural circumstances in which their children live. In contrast, their children are treated as victims of their parents (Goldson, 2002).

These trends in policies and popular perceptions of causes of poverty motivated us to subject them to critical scrutiny. We decided to invite parents in families in poverty situations to participate in our research project. We included their life knowledge through conducting family history research as the basis to identify which social work interventions they experienced as meaningful for their mobility out of poverty (see Schiettecat et al., 2016).

Reference:

Schiettecat, T., Roets, G., Vandenbroeck, M. (2017). What families in poverty consider supportive: welfare strategies of parents with young children in relation to (child and family) social work. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), 689-699.

Jacquet, N., Van Haute, D., Schiettecat, T., Roets, G. (2022). Stereotypes, conditions, and binaries: analysing processes of social disqualification towards children and parents living in poverty. British Journal of Social Work Stereotypes, conditions and binaries: Analysing processes of social disqualification towards children and parents living in precarity | The British Journal of Social Work | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

4. Partners

The partners we invited were three types: the university-based teachers/researchers, families and, in particular, mothers and fathers in families experiencing poverty, and social work professionals in child and family social work.

The co-coordinating (university-based) teachers/researchers had pre-existing relationships and were already well established with the relevant social work organisations, who supported the families on an everyday basis for a long time. This was important for ethical reasons: while doing the participative research, we could rely on the trusting relationships we had developed with these partners through their involvement in previous teaching and research.

The service users as research participants were recruited with the help of these social work organisations. We asked them to recruit families ready to participate, with whom they had given support and who experienced financial difficulties over time. After these preliminary contacts, we negotiated directly with the families and obtained their informed consent. We conducted open qualitative in-depth interviews with parents of young children who had experiences with a diversity of social work interventions. The families had several children, preferably one of their children being aged between zero and three years old. In the course of the research process, we interviewed 14 parents (ten mothers and four fathers) from nine different families. Some parents only intermittently joined the conversation, yet nine parents (seven mothers and two fathers from seven families) were interviewed more extensively.

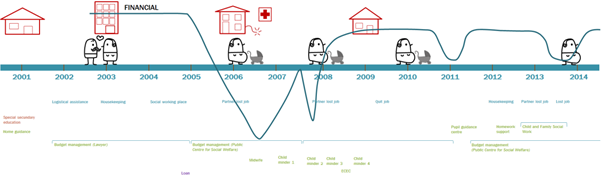

Within a series of two to four conversations, which lasted one to five hours, parents told their life stories and their experiences of social work interventions. All 27 interviews were fully audiotaped and transcribed, and the researcher shared the reconstructed family histories again with the parents to refine the findings and storylines. The process of working together to (re)construct the parents' family histories steered us, by mutual agreement, to an attempt to visualise their life histories. This allowed us to deepen our understanding of the poverty situations the research participants lived in. We were able to document existing resources, events and key incidents at specific turning points (Millar, 2007). Our life history approach resulted in a complex mosaic of life experiences, which were pieced together and contextualised through constructing an individual lifeline in close collaboration with the parents. These lifelines ran through each research process as a common thread and were gradually corrected, elaborated and refined. This allowed us to gain a profound understanding of how transitions, events, and resources (including social work interventions) led to these transitions being experienced by these families.

ONE'S OWN POSITION

We deemed a participatory yet also reflexive approach in social work research particularly vital since family history research "is a practice that is not merely enacting a prescribed research role according to steps in a manual" but requires a recognition of the reflexive role of the researcher (Roberts, 2002: 173).

We wanted to take into account the power imbalances typically implicated in participatory knowledge production about the complex social problem of poverty. Our impetus for using a participatory approach to social work research has been to reconfigure the power relations implicated in knowledge production by emphasising the participation of the research partners in co-constructing knowledge. Nevertheless, determining how to interpret and write about the research insights 'is in the hands of the researcher and not in the hands of the researched, the interviewed' (Krumer-Nevo, 2002: 305).

We follow Krumer-Nevo (2009: 282), who states that many scholars engage with participatory research approaches 'but do not specify the process through which they had produced it (...). The role that people in poverty took in them is not clear'.

For us, the life history research approach involved methodological and ethical dilemmas, complexities and ambiguities (D'Cruz and Jones, 2004), which required the necessary openness to discuss our doubts and considerations emerging during the research process (Roose et al., 2016).

References:

Roose, R., Roets, G., Schiettecat, T., Piessens, A., Van Gils, J., Pannecoucke, B., Driessens, K., Desair, K., Hermans, K., Op de Beeck, H., Vandenhole, W., van Robaeys, B., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2016). Social work research as a practice of transparency. European Journal of Social Work, 19(6), 1021-1034.

Schiettecat, T., Roets, G., Vandenbroeck, M. (2018). Capturing life histories about movements into and out of poverty: A road with pits and bumps. Qualitative Social Work, 17(3), 387-404.

5. Approaches and strategies

We adopted a family history approach in which the welfare strategies, struggles, hopes and aspirations of parents with young children moving into and out of poverty and their experiences with social work were explored retrospectively. Retrospective approaches to qualitative longitudinal poverty research involve collecting data "about their past experiences and life changes" (Alcock, 2004: 403). They can provide considerable detail about circumstances and structural resources and constraints.

Family history research allows research partners to tell their life history 'not based on predetermined responses to predefined objects, but rather as interpreters, definers, signalers, and symbol and signal readers' (Bogdan and Biklen, 1998: 25). Therefore, we did not use a pre-established definition of mobility into and out of poverty in the life histories of the families but approached it as a "sensitising concept", which gradually gained meaning through the research interaction (Bogdan and Biklen, 1998). Blumer (1954: 7) explained that "sensitising concepts" give the user 'a general sense of reference and guidance in approaching empirical instances. Whereas definitive concepts provide prescriptions of what to see, sensitising concepts merely suggest directions along which to look'. They still require processes of negotiation and interpretation. The involvement of both the researcher and the people concerned in the interpretations of their life stories evidences the potential power gap between the researcher and researched when studying the life worlds of people who belong to marginalised groups in terms of their material, social, and symbolic resources (Krumer-Nevo, 2002, 2009).

Power relations in the family history research project emerged surprisingly and at different stages of the encounters with the parents. In what follows, we present an exemplary vignette of one family's reconstructed and visualised life histories while working with the mother and father (Wendy and Tom) and discuss the complexities involved in the construction process.

We were brought into contact with Wendy and Tom, both 33 years old, with the help of a child and family social work organisation that had almost ended its involvement with the family. At the time of the interviews, the couple had three children: a boy, seven years of age, and two daughters, respectively, three and five years old. Since both parents confirmed that they wanted to participate in the research project, we suggested arranging separate encounters. We reasoned that this way, their own meaning-making about transitions and support could be better valued.

Eventually, the researcher (Tineke Schiettecat) had three conversations with each parent. We rely on her personal field notes to detail the vignette:

I first met Wendy. When I entered the living room, she was busy ironing. Although the place didn't seem messy to me, she apologised that she hadn't cleaned yet. Wendy also spontaneously showed me some of their kids' toys, which she extensively demonstrated. A little later, I got a tour of the children's bedrooms. We took the time to admire more toys, and she drew my attention to a water stain above the window. Back downstairs, she taught me how to fabricate short summer pants from worn-out winter trousers and creatively fix the holes with patches from a low-budget store. I got the impression that Wendy wanted to prove to me that she was a good mother. Maybe she was, first of all, proud of what she could give her children despite difficult living conditions. Maybe she was nervous about the interview and didn't really know how to react. Or, maybe, her spontaneous, somewhat defensive attitude said something about how she was used to being approached by social services. An hour passed before I could find an occasion to explain why I actually came to visit her. Until then, I kept the recording device switched off. This unexpected start of the interview exemplified how the mother and I were entangled in subjective processes of interpretation based on the perceptions of the other, our own positioning, and the focus of our meeting. While clarifying our main topics of interest, during the following conversations, Wendy and I together (re)constructed and visualised her life trajectory. Again, this process provided useful tools to deepen the talk about experiences of life events, transitions and support.

Figure 2. Life trajectory of Wendy.

The research process I followed with Wendy's partner, Tom, was much alike.

Figure 3. Life trajectory of Tom.

The factual data both parents mentioned showed many resemblances. For instance, they both mentioned living on a 'ticking time bomb', while referring to formerly bad and very unsafe housing conditions. Tom and Wendy did, however, not always focus equally on the same happenings or interventions. Moreover, their corresponding experiences and interpretations of life events also sometimes profoundly differed. The latter was clearly illustrated on the occasion when Tom told me without euphoria that Wendy was pregnant again.

I still have to overcome this. But it's easier said than done, overcoming this. (silence) I do admit it, it's hard for me. (...) There will be four of us ...Three was already a lot, but four! For me, that's something ...For me, that's too much.

A couple of moments later, after Tom had shared his view on the new family situation, Wendy entered the room. She was shining. Because, at that moment, I was there to listen to the meaning-making of Tom, I decided to focus on his perspective primarily and to greet Wendy the way I normally did, without referring to her pregnancy. During the further course of the conversation, Wendy stayed around. She repeatedly passed by the table, gave me something to drink, and finally enthusiastically asked me if Tom had already shared the big news. I wanted to respect both perspectives equally, but because they seemed directly opposite to each other, I found this quite difficult. Eventually, I decided to answer her question honestly while trying not to choose sides and then turned again to Tom.

While reflecting on our research strategy, we noticed a shift from 'giving voice' to a more collaborative attempt to generate and co-construct 'knowledge' with the parents and families involved. Our research process illustrates a transition from talking at to talking with people in poverty. Krumer-Nevo (2009: 290) describes this shift as 'the treating of the voices of the inside-researchers as knowledge [which] requires that researchers think anew not only about the content of their research but also about its form'. She asserts that treating people in poverty as having knowledge is the acknowledgement that they do not only have personal experiences ', but they do also have thoughts, sometimes critical ones, ideas and recommendations, and they are capable of analysing and theorising their situations, even if they do it in nonacademic language' (Krumer-Nevo, 2009: 291). The research participants were, for instance, challenging the original research intentions of the researchers and presented a more complicated and multifaceted picture of transitions into and out of poverty. The research participants' accounts also revealed how social, cultural, relational, symbolic and material dimensions and resources are always intrinsically interrelated.

6. Follow up activities

The research project has led to the representation and dissemination of the research findings, which were produced in an attempt to embrace the participation of the parents in our process of knowledge production.

For that reason, we considered that findings and representations draw the attention of social policymakers and social workers, who often perceive the individual child as the locus of intervention. Research findings are moreover often represented as causal explanations, in a 'bullet-point’-like way, and focus on facts rather than interpretative understandings. This can discredit the possibilities of democratic debate with actors in our society – including the families themselves – about the complexity of pursuing policy and practice to counter dynamics related to child poverty and about the ways in which policy and practice shape the structures and discourses that influence concrete circumstances of children living in poverty. During dissemination activities, we used the family histories and the visual representations to make sense of the messiness, ambiguity, and multi-layered nature of meaning in the stories while working with the audience. We advocated a perspective of social justice and equality as a point of departure. We raised contentious issues so that our research could provide further food for thought for actors who create the conditions under which children and parents in poverty situations live.

Nevertheless, we also realised that the weakest point of our research project consisted of the lack of renewed dialogue with the participating families involved during the representation and dissemination activities to create a forum for their ideas in relation to further actions. However, we lacked the funding and time to do this as part of the research project that covered only four years.