PARTICIPATIVE RESEARCH EXAMPLE FROM BELGIUM

5. Approaches and strategies

We adopted a family history approach in which the welfare strategies, struggles, hopes and aspirations of parents with young children moving into and out of poverty and their experiences with social work were explored retrospectively. Retrospective approaches to qualitative longitudinal poverty research involve collecting data "about their past experiences and life changes" (Alcock, 2004: 403). They can provide considerable detail about circumstances and structural resources and constraints.

Family history research allows research partners to tell their life history 'not based on predetermined responses to predefined objects, but rather as interpreters, definers, signalers, and symbol and signal readers' (Bogdan and Biklen, 1998: 25). Therefore, we did not use a pre-established definition of mobility into and out of poverty in the life histories of the families but approached it as a "sensitising concept", which gradually gained meaning through the research interaction (Bogdan and Biklen, 1998). Blumer (1954: 7) explained that "sensitising concepts" give the user 'a general sense of reference and guidance in approaching empirical instances. Whereas definitive concepts provide prescriptions of what to see, sensitising concepts merely suggest directions along which to look'. They still require processes of negotiation and interpretation. The involvement of both the researcher and the people concerned in the interpretations of their life stories evidences the potential power gap between the researcher and researched when studying the life worlds of people who belong to marginalised groups in terms of their material, social, and symbolic resources (Krumer-Nevo, 2002, 2009).

Power relations in the family history research project emerged surprisingly and at different stages of the encounters with the parents. In what follows, we present an exemplary vignette of one family's reconstructed and visualised life histories while working with the mother and father (Wendy and Tom) and discuss the complexities involved in the construction process.

We were brought into contact with Wendy and Tom, both 33 years old, with the help of a child and family social work organisation that had almost ended its involvement with the family. At the time of the interviews, the couple had three children: a boy, seven years of age, and two daughters, respectively, three and five years old. Since both parents confirmed that they wanted to participate in the research project, we suggested arranging separate encounters. We reasoned that this way, their own meaning-making about transitions and support could be better valued.

Eventually, the researcher (Tineke Schiettecat) had three conversations with each parent. We rely on her personal field notes to detail the vignette:

I first met Wendy. When I entered the living room, she was busy ironing. Although the place didn't seem messy to me, she apologised that she hadn't cleaned yet. Wendy also spontaneously showed me some of their kids' toys, which she extensively demonstrated. A little later, I got a tour of the children's bedrooms. We took the time to admire more toys, and she drew my attention to a water stain above the window. Back downstairs, she taught me how to fabricate short summer pants from worn-out winter trousers and creatively fix the holes with patches from a low-budget store. I got the impression that Wendy wanted to prove to me that she was a good mother. Maybe she was, first of all, proud of what she could give her children despite difficult living conditions. Maybe she was nervous about the interview and didn't really know how to react. Or, maybe, her spontaneous, somewhat defensive attitude said something about how she was used to being approached by social services. An hour passed before I could find an occasion to explain why I actually came to visit her. Until then, I kept the recording device switched off. This unexpected start of the interview exemplified how the mother and I were entangled in subjective processes of interpretation based on the perceptions of the other, our own positioning, and the focus of our meeting. While clarifying our main topics of interest, during the following conversations, Wendy and I together (re)constructed and visualised her life trajectory. Again, this process provided useful tools to deepen the talk about experiences of life events, transitions and support.

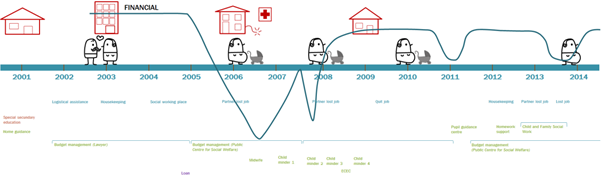

Figure 2. Life trajectory of Wendy.

The research process I followed with Wendy's partner, Tom, was much alike.

Figure 3. Life trajectory of Tom.

The factual data both parents mentioned showed many resemblances. For instance, they both mentioned living on a 'ticking time bomb', while referring to formerly bad and very unsafe housing conditions. Tom and Wendy did, however, not always focus equally on the same happenings or interventions. Moreover, their corresponding experiences and interpretations of life events also sometimes profoundly differed. The latter was clearly illustrated on the occasion when Tom told me without euphoria that Wendy was pregnant again.

I still have to overcome this. But it's easier said than done, overcoming this. (silence) I do admit it, it's hard for me. (...) There will be four of us ...Three was already a lot, but four! For me, that's something ...For me, that's too much.

A couple of moments later, after Tom had shared his view on the new family situation, Wendy entered the room. She was shining. Because, at that moment, I was there to listen to the meaning-making of Tom, I decided to focus on his perspective primarily and to greet Wendy the way I normally did, without referring to her pregnancy. During the further course of the conversation, Wendy stayed around. She repeatedly passed by the table, gave me something to drink, and finally enthusiastically asked me if Tom had already shared the big news. I wanted to respect both perspectives equally, but because they seemed directly opposite to each other, I found this quite difficult. Eventually, I decided to answer her question honestly while trying not to choose sides and then turned again to Tom.

While reflecting on our research strategy, we noticed a shift from 'giving voice' to a more collaborative attempt to generate and co-construct 'knowledge' with the parents and families involved. Our research process illustrates a transition from talking at to talking with people in poverty. Krumer-Nevo (2009: 290) describes this shift as 'the treating of the voices of the inside-researchers as knowledge [which] requires that researchers think anew not only about the content of their research but also about its form'. She asserts that treating people in poverty as having knowledge is the acknowledgement that they do not only have personal experiences ', but they do also have thoughts, sometimes critical ones, ideas and recommendations, and they are capable of analysing and theorising their situations, even if they do it in nonacademic language' (Krumer-Nevo, 2009: 291). The research participants were, for instance, challenging the original research intentions of the researchers and presented a more complicated and multifaceted picture of transitions into and out of poverty. The research participants' accounts also revealed how social, cultural, relational, symbolic and material dimensions and resources are always intrinsically interrelated.